Building on soil in Big Sandy

Bob Quinn is sitting on his front steps, pulling on a pair of worn work boots.

Small lilac bushes surround his brick house, their blooms months past. The lawn is tidy and green, kept neatly cropped by Quinn’s wife of 50 years, Ann.

Quinn stands, puts on his cowboy hat, and walks down the concrete driveway. At its end, he turns right on the dirt drive parallelling the shelter belt of spruce, pine, ash and lilac his father planted in the 1950s to protect the homestead from the prevailing west wind. To his right, beyond the white picket fence surrounding his backyard vegetable garden, Rattlesnake Butte is visible 4 miles to the east, a hazy blue outline through the smoke of early August wildfires. The brownish-white air obscures the rest of the Bear Paw Mountains.

At the end of the shelter belt, Quinn, 73, steps off the road into his dryland vegetable and crop experiment.

“So, this is a disaster,” he says, looking out over the plot. “This is an experiment that didn’t work very well.”

The son and grandson of farmers, Quinn grew up here, 13 miles south of Big Sandy, population 605. A half-hour drive north of Judith Landing on the Missouri River, his family’s farm is located in the Golden Triangle, a region in north-central Montana known for producing high-protein wheat. Quinn ran a diversified organic cropping operation here from 1986 to 2018, and like most farmers, he’s always looking for new ways to do things. Unlike many farmers, he has a doctorate in plant biochemistry from the University of California, Davis.

He walks over to the safflower plot and kneels. The plants look like spindly lollipops sticking out of bare dry earth, their green, ball-shaped seedheads the only thing left on the tan stalks. Grasshoppers, which destroyed crops across Montana this summer, have eaten the leaves and flowers and are starting on the heads.

Quinn breaks one off and, having forgotten his knife, uses a rock to split it. He spreads the halves, showing the triangular white seeds.

“Even though the plant is completely denuded, the seeds are maturing,” he says. “It might not be a great crop, but there is a crop.”

Instead of seeding the safflower in April or May, per usual, Quinn planted this plot during a warm spell in January. The crop was far enough along that it had bloomed and begun forming seeds before the grasshoppers got to it. While still unusual, thawed winter ground is becoming more common, Quinn says, noting that several years ago he successfully seeded winter wheat in January.

QUINN STARTED this research pilot plot in 2007 as part of another experiment. Like more than 300,000 acres in Montana, portions of the Quinn’s land are high in saline, and the common practice of keeping ground fallow to preserve water for the following season has caused salinated ground water to seep up to the surface in places. There, it dries and leaves a salt layer that sterilizes the soil. Quinn and his father planted alfalfa around seeps, gradually shrinking them as the deep roots captured the water.

Knowing there was still extra water beneath the surface of a reclaimed seep, Quinn was curious if he could grow vegetables normally grown in Montana with irrigation. He planted potatoes, squash and onions at various distances from the middle of the seep, seeking a sweet spot low enough in salinity with just enough subirrigation. For the experiment’s control, he planted the same vegetables in a dryland crop field. While the seep-planted vegetables grew poorly, those in the control plot did surprisingly well.

Since then, he’s continued experimenting with the dryland vegetables as part of what he now calls Quinn Organic Research Center. The research plot totals 4 acres and includes a dryland vegetable plot, his irrigated vegetable garden, an orchard, various crop trials, and a type of intermediate wheatgrass trademarked as Kernza, an experimental perennial grain crop that can improve carbon sequestration and reduce erosion. To replenish soil nutrients, he seeds a cover crop “cocktail” of peas, grains, lentils, vetch and barley on half of the plot each year, tilling it in as green manure in June, when the legumes have maximized their nitrogen fixation, and before the cover crop has used much of the soil’s water.

Quinn’s experiments produced the highest yields when the dryland vegetables had three times more space than the corresponding irrigated vegetables, allowing them to absorb enough water from the soil and rain. Most years, the dryland potato and tomato net yields equal their irrigated counterparts.

Quinn stands and walks through a patch of knee-high kochia, a weed that’s reducing crop yields across the Great Plains, especially as it becomes resistant to herbicide. Grasshoppers spring out with each step.

“Every flag here was a melon or a cantaloupe, or a squash,” he says, pointing at blue flagging. “[After the grasshoppers took them out], I didn’t really keep up with the weeds and just let it go.”

Half the potato plants are gone, demolished by grasshoppers before they could form tubers. Colorado potato beetles dot the remaining plants, bright orange larvae and black-and-white striped adults eating leaves and stems both. Ragged cornstalks bear almost no fruit, but beside them, a few watermelon vines hold six-inch melons.

AS WITH the majority of Montana and much of the West, drought conditions this summer meant harvests were smaller and earlier than usual. At Quinn’s farm, May brought a huge snowstorm, but then only 3.56 inches of rain fell between April and July, as compared to the mean of 7.14 inches in Big Sandy over the last 100 years. On July 12, a severe hail and wind storm west of town upended semi trucks, dented grain bins and destroyed barley and wheat crops. By late September, his yields in this plot were around 20% of normal.

In a year like that, harvesting any crop at all is a success. And looking forward, dryland crop research like Quinn’s could become an increasingly valuable part of food production as drought and a volatile climate continue to make Montana’s growing season drier and less predictable.

But it’s not a magic bullet.

“He’s finding varieties, general crop spacing and those kinds of things that work on his farm, [but] when you’re growing these things organically, you’re depending on a lot of ecological processes, and they might operate quite differently on a farm down the road, especially farms that are out toward the edges of his region that have a different climate than he does,” said Montana State University agroecologist Bruce Maxwell, who’s worked with Quinn over the years. A leading researcher in weed biology and the intersection of agriculture and climate change, Maxwell is currently studying how small grain growers in the Northern Plains can improve farm profitability and sustainability by gathering data on their own farms.

Maxwell explained that ecological processes exert a heavy influence on organic systems in particular due to climate, land management history and biology both above and below ground.

“But it’s at least a starting point, that’s the beauty of it,” Maxwell said, noting that Quinn is exploring a spectrum of food crops unlikely to be tested or experimented with on MSU’s research center farms, which tend to focus on commodity crops.

“Ultimately, it takes really local testing and doing repeatedly what he does in the way of experimentation in a lot of places,” Maxwell said, “because you’re dependent upon ecological processes, and ecology is time-specific, site-specific and history-specific.”

Quinn aims to grow this pilot plot into a full-fledged research center that will create jobs, dovetail with local markets, and help farmers become more resilient in the face of what he calls “climate chaos.” It’s already spawned a sister project that plans to provide more locally produced food to Big Sandy and surrounding Chouteau County.

He’s been through this process several times before. The research center is the latest in a series of projects Quinn spearheaded over the past 35 years, working with partners both locally and around the world. Built largely on organic agriculture, they range from his own organic farm to the creation of a new international grain market, a grain processor and elevator, an oilseed press, and the snack food business Big Sandy Organics, which is expanding rapidly under new ownership. Each has encountered roadblocks and failures, and all have grown beyond Quinn. Now they’ve evolved into a loosely connected ecosystem of markets that are benefitting small town farmers and their communities, including Big Sandy.

BOTH ON and off the farm, Quinn’s career exemplifies how investing in fundamentals — soil, business and community — can spark entrepreneurial innovation that helps producers access new markets, create jobs and, increasingly, rebuild local commerce in rural Montana.

A tractor drives by the research plot, kicking up dust, followed by a semi truck with a load of hay. The semi honks.

“Those are the guys who are leasing my farm,” Quinn says.

Now retired from large-scale farming, he rents most of his 4,000 acres to two former employees, Seth Goodman and Chad Fasteson. They’ve bought Quinn’s machinery and are running their own organic operation here, and also lease another 4,000 acres nearby, 1,000 of which they’ve been unable to farm organically due to decades of poor management and the resulting weed pressures, Goodman said.

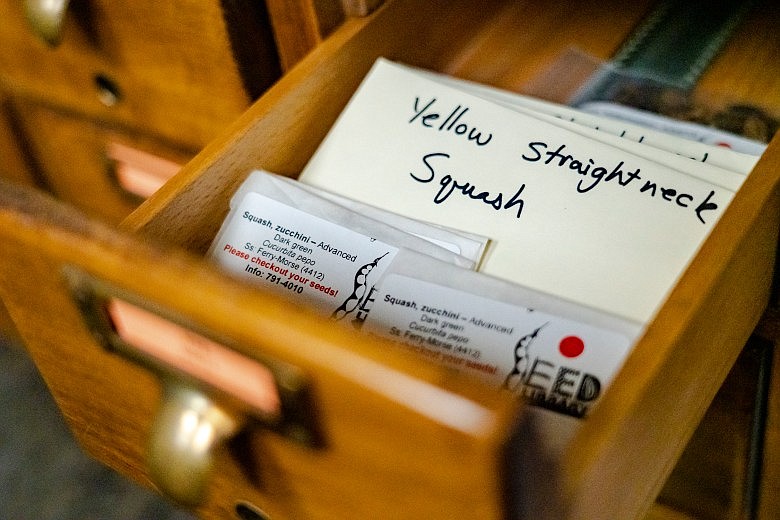

Another young couple doing business as C&S Produce leases a smaller parcel where they grow organic potatoes and squash for local and regional markets.

“What I’m trying to tell and show is that there are lots of ways to make a living in agriculture besides coming back to the farm and buying [out] the neighbors,” Quinn said. “That’s been the model the last 50 years … rather than make more with what you’ve got by diversifying your markets and your products.”

Big Sandy is a community whose past and future are built on soil. The town’s population grew at a healthy clip from 1950 to 1960, when it peaked at just over 950. Back then it was thriving, with a department store, a hardware store, a movie theater, an ice skating rink and five operating grain elevators.

By the late 1970s, many local businesses had shuttered and residents had moved away, pushed out by an industrial agriculture system that essentially exported wealth alongside commodities.

Today, Big Sandy’s elevators sit empty along a railroad spur that’s used to store train cars, and the 20 or so jobs the elevators supported are gone. Local farmers selling into commodity markets now haul their grain to centralized elevators in Fort Benton, Rudyard, Havre, Chester or Great Falls, 35 to 80 miles away. At the same time, land prices in Big Sandy have continued rising.

“That means it’s almost impossible for a young person to begin farming or ranching without family help,” said Shane Ophus, a real estate broker and farm and ranch auctioneer in Big Sandy.

COMMODITY FARMERS play a major role in Montana’s economy and in international food production. Because margins can be thin in the commodity market, economies of scale are usually what allow farms to stay profitable. But a growing number of producers in Big Sandy and around Montana are exploring another strategy for keeping degraded agricultural land in production: They increase their soil fertility, reduce operating costs, and try to sell into higher-value markets. Some are organic, like Quinn. Others continue to spray weeds and pests while taking steps to reinvest in ecological resilience by implementing regenerative soil-building systems like no-till, cover cropping, crop rotation and livestock integration. Quite a few farmers in Big Sandy have tried organic, but only a handful have stuck with it.

“I would admit that I’m not an organic total believer yet,” said Big Sandy Mayor Shaud Schwarzbach, who’s also the vice president and loan officer of the local bank branch and a farmer himself.

While 80% of the loans Schwarzbach processes are agricultural, he estimates that only about 10% of the area’s production acreage is certified organic. He also says there’s still a cultural divide between organic and conventional producers.

“I think [organic is] the way it should be, and the economics have been there,” Schwarzbach said, explaining that his hesitancy comes from knowing organic growers who’ve struggled with weeds and insect pests, incurring huge costs to transition to organic only to surrender their certification when they can’t make it work.

Like so many in Big Sandy, farming is a way of life for Schwarzbach.

“I got the bug, or the disease, sometimes it’s called. My great uncle farmed north of Gildford, which is on the Hi-Line, too, and spending weekends and weeks in the summer out there with him, he taught me how to drive and drive tractor when I was 5 years old, so he kind of implanted that love in me.”

Seeing the market for organics through early customers is what convinced Quinn to convert the family farm. After he and his father began transitioning to organic in 1986, they typically harvested less than their conventional-farming neighbors, but gleaned higher profits than their own conventional crops produced due to lower costs and higher prices. Instead of using fertilizer and pesticide, they rotated both cash crops and nitrogen-fixing cover crops like alfalfa, creating soil fertility and competing against weeds.

Also in the mid-1980s, Quinn and a group of other Montana organic pioneers including David Oien from the lentil processor Timeless Seeds helped establish Montana’s organic statute, making it the fourth state to have an organic law. In the 1990s, Quinn sat on the USDA’s first National Organic Standards Board, which built a framework for the eventual implementation of the program in 2002.

None of it happened in a vacuum. Both he and his wife, Ann, are quick to say that while Quinn was farming and growing his businesses, Ann did most of the work raising their five children.

As with the dryland research plot, these ventures also came with challenges and failures.

THERE’S BROAD public interest and government support in Montana for value-added ag, which the USDA defines as “produced in a way that increases value, for instance, according to organic certification requirements, and those that were physically altered, for instance, strawberries that were made into jam.” The state agriculture department doesn’t track small business growth in the value-added sector. Anecdotally, though, it’s said to be expanding, especially since the pandemic supercharged demand for local food.

But building a business can be hard, especially in rural Montana, where there is often a more conservative attitude toward the risks that come with entrepreneurship, and a less robust network of entrepreneurial support, said Tara Mastel, who runs the MSU Extension Reimagining Rural program.

“You need the supports around those rural entrepreneurs to help them see the vision, develop the skills and move forward with their projects,” Mastel said.

Adding value may be a challenge for individual operators, but the rewards can travel well beyond the farm through a ripple effect of community benefits.

“Any time we have somebody that’s on the cutting edge, it’s a really bloody place to be, because you’re going to catch all this other stuff about whether this innovation is going to work,” said MSU agricultural economist George Haynes. “But this is the dynamic you need to push an economy along, because they’re willing to take those risks. It all comes from being willing to take what hurdles are in front of them and jump right over them and show people it’s going to work.”

In 2021, the federal Farm Bill set aside $25 million in USDA funding for organic research, and by 2030 that number will cap out at $50 million. It’s a small percentage of the $3.3 billion the agency budgeted in 2021 for all agricultural research. In Montana, multiple MSU affiliates are doing organic vegetable and dryland crop research and education, including the Western Agricultural Research Center in Corvallis, the Horticulture Farm at MSU-Bozeman, and the Central Ag Research Center in Moccasin. Still, that research is minimal compared to university research on conventional ag, so there’s much less knowledge about how to fight drought, weeds and pests in organic systems. But as weeds become increasingly herbicide-resistant and climate change intensifies, the knowledge gained from organics may be key to sustaining food production and security in the future.

“[With organic systems] you have to react quicker to problems that are coming, because you just can’t have a spray plane come in and solve something that you didn’t take care of earlier,” Quinn said. “You have to be ahead of the disaster and hope you can mediate it. And you need to be diversified. Really, completely diversified. Because some years there’s just nothing we can do right now.”

Those lessons in diversification and risk reduction are why Quinn and Thomas Dilworth, who bought Quinn’s snack food business Big Sandy Organics with his wife, Heather, are working to provide more locally grown food to their community.

“It’s going to be needed soon if the drought continues,” Dilworth said. “These big cities where people really believe that groceries come from the grocery store shelf, they’re going to suffer, and we have to have active solutions in place.”

Like much of Montana, Big Sandy grew a large portion of its own food as recently as the mid-20th century. Today, some residents raise backyard gardens and the grocer carries local food from Pearson’s Big Sandy Cantaloupe and C&S Produce, as well Krackin’ Kamut snacks from Big Sandy Organics and safflower oil from another of Quinn’s businesses, The Oil Barn. Still, budget limitations and food safety regulations combined with convenience, culture and consumer preference mean the only way local food service entities can operate in the current market is to receive regular deliveries trucked in by large distributors.

UNDER QUINN'S proposal, the research center and other local producers would establish a year’s supply of long-term storage items already grown locally, like wheat, barley, cooking oil and storage vegetables, for the approximately 1,200 residents of northern Chouteau County, starting in 2022. He and Dilworth are seeking grant funding to establish irrigated plots and hoop houses for fresh vegetables in 2023. Meat, dairy, eggs, honey, berries, fruits and nuts would follow. The goal is to match the prices people pay for food now.

They’re in conversation with potential partners including the school, medical center, grocery store, senior center and two local restaurants. Several were already considering something similar, and all were open to the idea, but many also had concerns and questions.

Still, Quinn sees progress.

“Thirty years ago, I wouldn’t have gotten this kind of reception,” he said. “I’m not pushing uphill quite as hard against so much tradition that says there’s no reason to change anything. Thirty years ago, fewer people had already gone broke. Everything was really rosy with industrial ag.”

Back then, the organic market wasn’t well-defined, similar to the emerging regenerative industry today.

“What’s transpired in organics is that when we first started out there wasn’t a market,” said U.S. Sen. Jon Tester, who farms organically on his family’s 1,800-acre T-Bone Farms west of Big Sandy.

“If you’re starting a new enterprise, or if you’re raising a crop,” Tester said, “you’ve got to have some infrastructure behind it to be able to make it and allow it to be successful and permanent.”

For a rural ag town like Big Sandy, that infrastructure has already created jobs and economic vitality. Since taking over Big Sandy Organics in early 2021, Dilworth has secured large national deals and begun planning a several-million-dollar expansion. He’s also now manufacturing custom products for other Montana farmers, both organic and conventional, aiming to help them establish value-add facilities in their own communities. The business has already grown from three to five full-time employees, and the plan is to have 15 or more by 2023. To get there, Dilworth is working with the town to secure more land and water, both of which are in short supply.

Quinn imagines the research center and local food project as models ripe for duplication around the state, adjusted for different growing conditions, resources and local culture. For now, as with all his projects, he’s testing the water.

“My philosophy is to start small enough so that if it does fail, it doesn’t sink your whole ship,” he said. “The farm was the ship, and these little boats we launched, if one went down, you still had the ship.”