Lakeside cartoonist a player on the political world stage

From channeling his anger about the 2008 banker bailout into political cartoons, Ben Garrison of Lakeside has become one of the nation’s most popular online political cartoonists, even making waves internationally.

“Abandon Ship,” a cartoon about last week’s Brexit referendum, has been viewed more than 300,000 times, was retweeted by British businessman and politician Lord Michael Ashcroft and drew ire from a Guardian columnist for its portrayal of Muslim refugees.

A political cartoonist told Garrison early in his career as a graphic artist that he was too nice a guy to do caustic editorial cartoons.

“When the bankers got bailed out, that’s when I discovered my meanness,” Garrison said.

Although he hadn’t drawn a cartoon in more than 20 years, Garrison picked up his pen and started drawing anti-Federal Reserve cartoons in 2009. It was just after he and his wife moved to Montana from Seattle, where Garrison worked at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer until it switched to an online-only format.

His first cartoon to go viral was 2010’s “The March of Tyranny.” Drawn with a Sharpie in three hours, it now has been translated into multiple languages and seen by millions. It depicts the global elite bankers as the all-seeing eye in the triangle, using the mainstream media to bark out marching orders to vote left and right — one of his many cartoons to go beyond the typical donkey vs. elephant meme.

Since then, his cartoons have been shared online by political commentator Ann Coulter, Donald Trump adviser Dan Scavino and thousands of others. Reality TV star Kylie Jenner retweeted his “Citizen Cattle” cartoon that calls out GMO foods and big pharma. He has been interviewed on “The Alex Jones Show,” with an estimated listenership of 2 million, and his cartoons are frequently published on financial blog ZeroHedge.com.

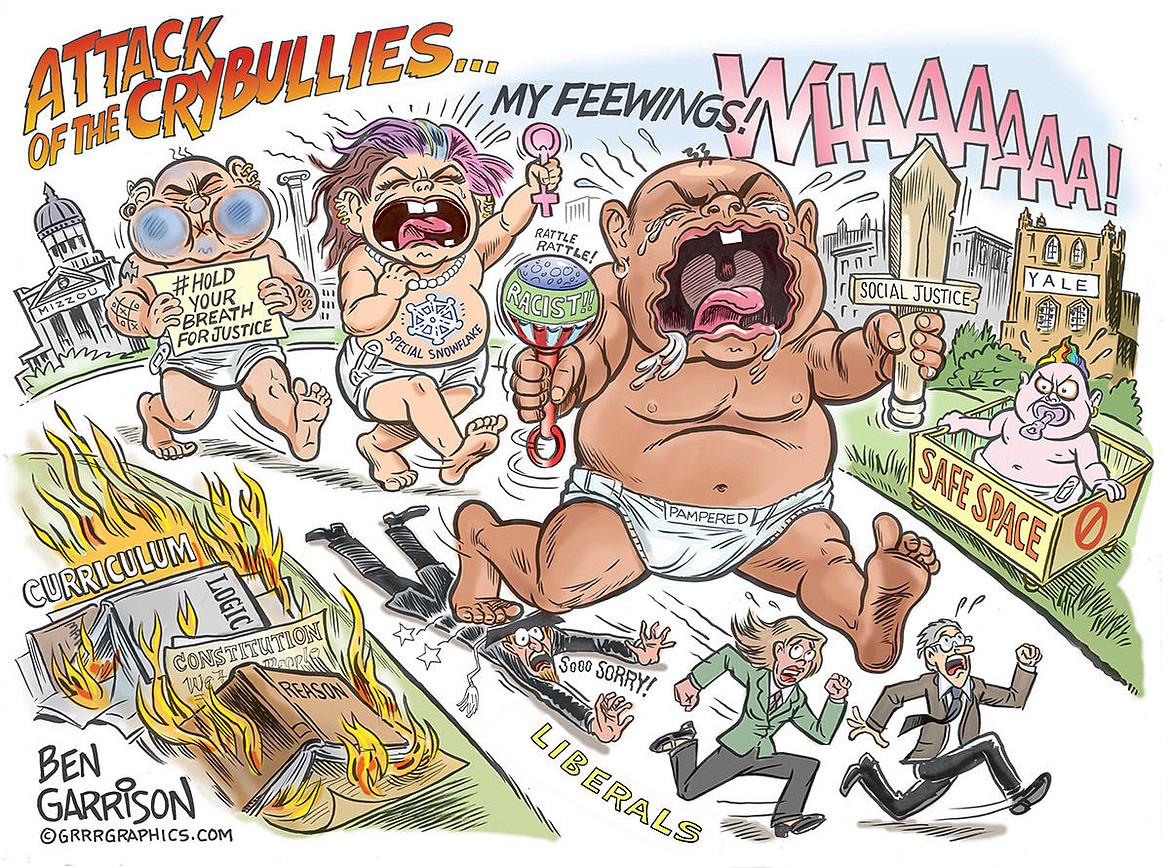

A recent theme in Garrison’s cartoons is political correctness and social justice warriors (SJWs), a pejorative term used to describe left-wingers — typically college students — who push for change using protests, threats and shutting down events.

“Attack of the Cry Bullies” from November 2015 shows college students as giant babies, one in a “safe space” playpen. Books on logic and reason burn in a fire in the foreground.

“I do cartoons that are anti-political correctness, anti-social justice warrior, because really what political correctness is is fascism with manners,” said Garrison, a Libertarian and believer in free speech.

As if proving his point, SJWs on Facebook reported the cartoon en masse, leading to the removal of the image and a 24-hour ban of Garrison’s account. Due to his dedicated following on Twitter, the story of the ban went viral, adding evidence to what many on the right see as Facebook’s censorship of conservatives.

But to Garrison, the outcry about some of his cartoons is a sign that his satire is effective.

“A good editorial cartoon is like a switchblade,” he said. “It’s simple, to the point, cuts deep and leaves a scar.”

Trending with the Trump train

Since Donald Trump entered the presidential race, Garrison’s pro-Trump cartoons have helped expand his audience.

“I disagree with him on some of the issues. But when he came out and said he’s willing to audit the Federal Reserve, I said, ‘He’s worth supporting,’ especially since he’s not afraid to be politically incorrect. That’s a huge breath of fresh air,” Garrison said, adding, “I wish he would renounce his support for the NSA.”

The cartoons of Trump and those exposing political correctness have made Garrison’s work especially popular among young conservatives who share the images on social media.

“People don’t have long attention spans” nowadays, Garrison said. “But an editorial cartoon is going to get attention and they’re actually going to spend the few seconds it takes to read it.”

One of Garrison’s cartoons portrays Trump slaying the dragon of political correctness. “The Great Wall of Trump” shows the presumptive Republican nominee knocking out opponents ranging from Pope Francis to establishment Republicans. Garrison’s “If You Build it, They Won’t Come” T-shirt — showing Trump peering over a border wall—has been a big seller.

Critics of some cartoons call them racist and sexist, epithets that no longer bother Garrison. “Usually when someone starts calling you a racist, that’s designed to shut down free speech,” he said.

It’s also something he has in common with Trump. When Garrison hears people call Trump a racist or Hitler, “that means they don’t have an argument,” he said, “so they want to shut him down by calling him names.”

With Trump, “the more they called him the names the more popular he got,” Garrison said. The same thing seems to be happening with Garrison’s cartoons.

He and his wife’s business, GrrrGraphics.com, has expanded to selling prints of the cartoons and T-shirts. Garrison has been commissioned to do cartoons for some of the biggest celebrities in the online Libertarian movement, such as Stefan Molyneux with Freedomain Radio and YouTube pundit Sargon of Akkad, along with controversial Breitbart.com tech editor Milo Yiannopoulos.

Garrison will be featured as the Ace of Clubs in an upcoming Trump playing card deck, and his cartoons are included in the traveling art exhibition Trumpmania.

Tina Garrison, also an illustrator, handles the business side of GrrrGraphics, including selling the original cartoons on eBay. Via the crowdfunding site Patreon, more than 120 people are pledging a total of more than $1,000 a month to help fund Garrison’s work. Their goal is to get enough patrons for Garrison to do the cartoons full time.

Fans of his work in the Flathead Valley are unlikely to see any cartoons focusing on Montana politics, however. “The problem with that,” Garrison said, “is there’s no market.”

The high price of free speech

Garrison’s career as a political cartoonist and self-described “citizen-muckraker” hasn’t been easy. Less than a year after he started publishing his initial cartoons — mostly harping on the Federal Reserve and big banks — a group of online trolls started targeting his work. On one cartoon, they replaced the face of Ben Bernanke, then chairman of the Federal Reserve, with an anti-Semitic caricature of a Jewish man, turning the cartoon into one that looks like Nazi propaganda.

When Garrison complained to websites about the defaced cartoons being published with his name left intact, it made the situation worse.

“That was like poking a stick in a hornet’s nest,” Garrison said. “Then they all started defacing all of my cartoons.”

Anonymous white supremacists started creating “hate meme boxes”—using Garrison’s photo and attributing fake quotes to him that were racist and anti-Semitic. One person made a fake Kalispell obituary that claimed he had committed suicide. Like the trolls in fairy tales who live under bridges and harass travelers, online trolls have a mission of upsetting others by posting inflammatory material, solely to harass people for their own amusement.

Lawyers said the case was actionable, since the trolls’ actions went well beyond free speech into libel and copyright infringement. But a case would cost more than $100,000, given out-of-state court orders and the difficulty of proving a given person was typing at a computer, even if he or she had the Internet Protocol address. The Online Hate Prevention Institute helped get one defamatory page on Facebook taken down, but it was back again a few days later.

Garrison tried to ignore the trolls, but the fake images that came up in Google searches were hurting his freelance commercial art business. In 2014, he spent more than 100 hours trying to remove libel on the Internet, but it was “like trying to sweep the tide out with a broom.” From the summer of 2015 to January this year, he had no work, relying solely on his political cartoons and Patreon supporters for income.

“I was mad at the world, I was mad at myself, I was mad at everybody,” said Garrison. “And I almost considered stopping drawing the cartoons altogether. I said, ‘I lost. I lost to the Internet hate machine.’”

On the advice of a lawyer, Garrison wrote a book to clear his name, but “it was a flop,” he said.

With his wife’s help, Garrison continued the journey to recover his voice, sharing his story online, engaging with fans of his real cartoons and contacting previous clients to explain the trolling.

In September 2015, the accounts of one of the biggest trolls went silent. It turned out that Joshua Goldberg, a user with multiple online personas, had been arrested for providing bomb-making instructions to an FBI agent posing online as a Muslim extremist.

In addition to posting as a white supremacist, he also posed as an ISIS-affiliated jihadist and took credit for inspiring the May 2015 attack in Garland, Texas. When arrested, Goldberg was 20 years old and living with his parents in Florida.

Montana art

without clichés

Besides political cartoons, Garrison pursued another form of art shortly after moving to Lakeside — Cubo-Futurist paintings. His fine art reinvents the clichés seen in much Montana artwork into “Western Cubist” paintings that resemble the art of Picasso, Garrison’s favorite artist.

“I’m first and foremost a fine artist. I do the political cartoons out of anger. I do the fine art out of love,” he said.

For several years he was represented by Bigfork’s ARTfusion gallery—until the online trolls started harassing the owners.

Garrison is confident he will find another gallery for his fine art down the road. His paintings have sold as far away as England, thanks to a BBC article about Goldberg’s arrest that highlighted Garrison’s experience.

“Ironically,” said Garrison, “I would not have been known if not for this worldwide trolling.”

Amanda Lanier is a writer and blogger who lives in Whitefish.