An idea, an election and a beginning

The newspaper headlines in 1966 told Flathead County residents about deeper trenches in Vietnam, an increase in local mumps cases and the possibility of a college in Kalispell.

City council meetings and social gatherings became the grounds for voters to debate whether the valley needed higher education. Some said the county couldn’t afford the effort while others said it was long overdue.

“Education is the backbone of our nation,” Ernest Lunstad, a 1966 Democratic candidate for the Montana House, told the Daily Inter Lake. “Saying we cannot afford education is similar to admitting we cannot afford our people … But to keep from being accused of being blind ‘Do-Gooders’ we must do a little research.”

Years before the debate went public, Bill McClaren was creating supporters’ key arguments for higher education from his counselor’s office at Flathead High School.

McClaren was working toward a master’s from Columbia University for high school counseling. Before leaving New York to return to his hometown, he had to find a research project.

“My Columbia adviser said, ‘What are your students doing after graduation?,’ and I said, ‘I don’t know. I don’t think that question’s ever been asked,’” McClaren recalled.

When McClaren returned to the Flathead, school was already out for the summer. So he began calling the 191 graduates from that year. Some were already working on their neighbor’s farms or felling timber — like their parents had done before them.

Just 7 percent of the Flathead students were heading toward some type of higher education.

McClaren began calling other schools in the county and found similar statistics. Then he made some calls to Missoula counselors and learned 40 percent of their students were going on to post-secondary education.

“It sounded like we didn’t have a place to go to school and they did,” McClaren said. “That was the start.”

FOR YEARS, McClaren asked graduating Flathead County high school students the same question: “What’s next?”

“They didn’t have the money to even go as far as Missoula,” McClaren said. “We had an awful lot of talent, an awful lot of bright students, who hadn’t even thought about going on to school.”

McClaren brought his findings to the local school board in 1960. He announced that only 20 percent of Kalispell seniors planned to attend. Of those, roughly 7 percent were graduating with a four-year degree.

The chairman of the board, Owen Sowerwine, wasn’t happy with those findings.

“Owen said, ‘We’ve got to do something about it — now,’” McClaren said. “I think part of his concern was he had three kids. There was no problem about affording to send his kids to school, but there was an awful lot of kids in the valley who couldn’t go.”

Sowerwine had recently retired and decided to travel throughout the U.S. to find out what was happening to high school seniors across the nation. He learned the closer they were to some type of additional training, the more likely they were to enroll.

For three years, Sowerwine searched for a higher-education model that would work for the Flathead Valley. What he found was community colleges — they could balance the need for technical and academic programs.

“We finally had an idea,” McClaren said. “But we knew we needed to sell this to the community.”

They would need 20 percent of county voters to sign a petition asking for an election to establish a community college district.

FIVE KEY PEOPLE began the work to advocate for a community college. Sowerwine assigned each person an area to cover based on their position in the Kalispell social scene.

As the school counselor, McClaren visited each high school and elementary school.

Thelma Hetland, the Flathead County president of the Federated Women’s Club, was assigned the task of winning the women’s vote. She had two adopted children and wanted them to have an affordable education so they could be self-sufficient in the Flathead someday.

McClaren’s wife, Lois, recounted that in the mid-1960s, women had three main options: become a housewife, train for secretarial work, “or nursing, if they had the money.”

McClaren said Hetland sold the idea of more choices for women, “and she was a great salesman.” Hetland visited the 43 women’s clubs throughout the county carrying her message of a community college for all.

“I’m sure she’s the reason that it passed,” McClaren said. “Thelma got to the women in the county — she’d tell them, ‘you keep your husband home the day of the election — men just vote ‘no’ for things like this.’”

Les Sterling, owner of KOFI radio station, took to the airwaves. There wasn’t an hour that went by in the next several years that he missed mentioning the importance of college.

Norm Beyer, head of the local state employment agency, told business owners there would be more qualified workers if there was professional training available.

And Sowerwine took the men’s clubs and organizations.

On Jan. 31, 1967, Sowerwine arrived in Helena to present the state superintendent of public instruction a total of 3,168 Flathead signatures calling for an election to establish the college. They only needed 2,881 to get the vote.

“But there were people violently opposed to it,” McClaren said. “Somebody was going to have to pay for all this nonsense that was going to go on — it would raise taxes.”

Herman Ross, who became the first chairman of the board for FVCC, said during a school board meeting before the election that people didn’t understand the emphasis on vocational training at community colleges versus just academic training.

“My goodness, we have literally scores of students graduating from high school every year who simply aren’t ready for jobs,” he said, according to a Daily Inter Lake article.

Kent Newman of Columbia Falls said voters were concerned about the cost.

“In simple terms, it will cost a man with a $30,000 house the equivalent of three six-packs of beer a year,” he said.

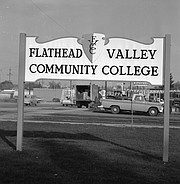

But when the votes were counted a week later, the college proponents had won by more than 1,000 votes, and headlines changed from possibility to certainty as planning began in earnest for Flathead Valley Community College to open almost immediately.

THE DAY after the election, McClaren sat next to FVCC President Larry Blake and Business Manager Leo Shepherd for the college’s first staff meeting.

“Dr. Blake began by announcing we would begin classes in two months,” McClaren said.

Blake said he would hire the faculty and tasked McClaren with recruiting students and Shepherd with searching for places to hold classes.

They rented 10 rooms from the high school for evening courses. The train depot, which now houses the Kalispell Chamber of Commerce, became the nucleus of the school.

“Leo went in with a fire hose, it hadn’t been used for quite a few years,” McClaren said.

The upstairs became administrative offices. The downstairs was the bookstore, student center and an art center.

Within a month, the college had roughly 200 faculty and student applications each, McClaren said. And each day more followed.

“We still had Les at the radio station and every hour he’d announce what courses we would offer, and sometimes he made them up,” McClaren said. “Even though my office had just been set up, by 9 a.m. I’d have two or three people waiting to see me.”

A black and white photo in the Daily Inter Lake from May 2, 1967, shows a woman paying the $10 registration fee to sign up for classes. The headline states, “College signs up mother as first student.”

The college had 611 students its first semester.

McClaren said if the college announced a need via the radio station, whether it was student housing, transportation or even theater props, community members would fill the void.

“We were figuring it out as we went,” he said. “The support was amazing, the president was optimistic, the faculty and the community were optimistic — we had no question it was going to last.”

Fifty years later, they have been proven right, and McClaren will be on hand Friday at a Founders Day celebration to accept the thanks of a grateful community.

Reporter Katheryn Houghton may be reached at 758-4436 or by email at khoughton@dailyinterlake.com.