The 'Godfather of girls track' led FVCC's trailblazing Mountainettes to championship

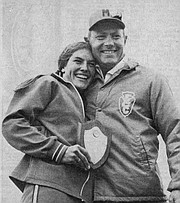

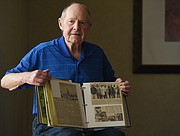

Neil Eliason may be the “Godfather of girls track” but the soft-spoken coaching legend didn’t earn the nickname the way the other dons did. This godfather ruled without an iron fist.

“Oh my gosh, he is such a wonderful man,” said Merridy Taylor, a sprinter at Flathead Valley Community College from 1970-72. “It was just a terrific experience to be coached by him.”

“He’s like a second father to me,” added Susan (Bronson) Loeffler, Taylor’s classmate and teammate. “He expected a lot out of you but he just had a very kind heart.”

“I never ever yelled at my kids or cussed them or anything like that,” Eliason said. “We all had a good relationship. I got on their butt but they knew they had it coming and I’d do it individually. I wouldn’t ever criticize them in front of the other kids.”

Whatever the means, Eliason, the athletic director, men’s and women’s track and field coach, a guidance counselor and financial aid officer for most of Flathead Valley Community College’s first decade, earned his “Godfather” status through a lifetime of breaking barriers and improbable successes, culminating with a national championship for Kalispell’s nascent community college 40 years ago next month.

BEFORE COMING to FVCC in 1969, Eliason was already a well-known figure in Montana track and field circles, no matter how small those circles were.

The Deer Lodge native grew up an asthmatic on a ranch there — “I knew that ranching wasn’t going to be for me,” he said — and began his coaching career in tiny Brady, Montana, before moving to Hot Springs in 1955. There, he brought his high-school physical-education class to what he called a track-and-field “play date” in Missoula and discovered “we were far better than anybody that was there,” he said, besting a field that included a team from the university.

In the early 1960s, Eliason came to Kalispell and started a club girls track and field program, since the sport was not sanctioned by the Montana High School Association until 1969. That club team, the Timberettes, quickly became one the standard-bearer for the state and one of the premier Amateur Athletic Union programs in the country.

So when Flathead Valley Community College decided to start up its girls track and field program in 1969, Eliason was an easy choice. He added the athletic director, guidance counselor and financial-aid officer jobs shortly thereafter and became one of the faces of the school in its early days.

His first FVCC Mountainettes team was just a duo, Kalispell’s Grace Willey and Joliet’s Linda Spaulding. Both girls, in a sign of things to come, would place at the 1969 National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) girls track and field meet and lead the two-member team to a seventh-place finish in a field that included mostly four-year schools. The two-member Mountainettes team placed higher than schools like the University of Tennessee and Florida State University.

Two years later, in part behind the running of Loeffler and Taylor, the Mountainettes would experience their first breakthrough on the national stage.

Loeffler, originally from Havre and the one who dubbed Eliason “the Godfather of girls track” in an interview earlier this month, anchored a 440-yard relay team that won the 1971 NAIA national championship in Cheney, Washington, out-dueling teams from Texas Tech University, UCLA and other prominent four-year schools.

Taylor was the third runner on that relay, handing the baton to Loeffler in second place before the anchor runner overtook the leader just before the finish line.

“Well, I was the slowest one on the team but I was on the team,” Taylor recalled with a laugh. “I just remember practicing our hand-offs, practicing our hand-offs, we practiced those for months in preparation for that meet.”

Loeffler, who has become a coaching legend herself in 43 years at Bigfork High School, also remembered the relentless hand-off work that Mr. E, as his athletes called him, put them through.

“I still coach this way because of it,” she said. “He demanded perfection on those hand-offs because he knew what we lacked maybe in speed against these guys we could get done with hand-offs.

“And I tell my kids to this day, and it’s true, if you can get a hand-off you can beat kids that are faster than you.”

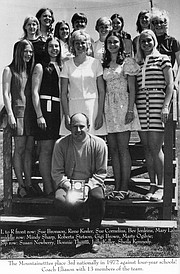

Mindy (Sharp) Harwood and Roberta Tognetti ran the first two legs of that race, and the quartet nearly won a second national championship, finishing as runner-up in the 880-yard medley relay. The team that year finished fourth in the nation, and one year later FVCC would return to the NAIA national meet and finish third, again matching up with the nation’s best college programs, regardless of size.

Shortly thereafter, the National Junior College Athletic Association was founded and the Mountainettes had a chance to compete against other two-year schools on a national stage. It didn’t take them long to make a big impression there, either.

The 1976 FVCC team finished second in the country, just seven points behind eventual champion Dodge City Junior College in somewhat controversial fashion when the Mountainettes’ medley relay team was disqualified for leaving its lane. Had the result been allowed to stand, FVCC would have gone home a national champion as a team for the first time in the school’s history.

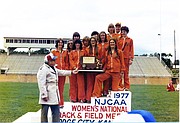

In 1977, the Mountainettes didn’t leave the result in any doubt.

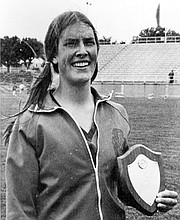

That team annihilated the competition at the national championship meet in Dodge City, Kansas, and piled up 106 points, 52 more than their closest competitor. Carla (Heintz) Swearengen won the individual championship with 33 1/2 points behind first-place finishes in the 100-meter hurdles and 400 hurdles, a second-place finish in the long jump, and was part of a victorious mile relay team.

Less than one month later, the Mountainettes’ sustained run of success came to a sudden end.

AS THE world of intercollegiate athletics underwent a paradigm shift and women’s sports became more and more important to the large, four-year colleges, schools like FVCC found themselves on uneven footing.

Eliason’s track programs, like most of the others at FVCC, had to be partially self-funded during their existence and it required the then-coach to be a bit creative.

“I needed to go to a junior nationals (one year) and I needed $6,000 to get tickets,” Eliason recalled. “And I went to the cafe where all of the businessmen were … and I left there with $7,500.”

Despite regular support from the community, by 1977 the resources and scholarships offered by larger schools meant it would be tougher and tougher for Eliason and the school to compete on a high level.

So in June 1977, the Mountainettes coach accepted a job as the head girls track and field coach at Montana State University, where he remained until 1985. FVCC toyed with discontinuing the program that summer but eventually allowed it to continue for two more seasons before the end came permanently in 1979.

Still, the impact Eliason and his girls had made on track and field in Montana lives on. He and his FVCC team used to travel throughout the state to hold track and field clinics at Montana high schools, and to this day the state still regularly produces some of the top female runners in the country, the latest being Glacier High School’s sensational junior distance runner Annie Hill.

Much of that credit, to hear his former runners tell it, belongs to the man they call the godfather.

“I felt honored to be able to go to a school and to be able to run and that girls were more important — it’s sad — but we were more important than the boys,” Loeffler said.

“There were no sanctioned girls sports,” Taylor added. “It wasn’t until I was a junior and track was the first one and I know that it only happened because of the work that Mr. Eliason did ... That women finally were able to participate in something.”

Entertainment editor Andy Viano can be reached at (406) 758-4439 or aviano@dailyinterlake.com.