2016: State opened doors to sharing economy

In 2016 Montana opened its doors to the sharing economy, a new form of business that regulators have been wrestling with for nearly the past decade.

In a sharing economy, sometimes called the gig economy, businesses don’t require much oversight. People on either side of the connection are most active: those who are looking for some additional income can share assets with people who are looking for a ride, a room, a couch or a boat. Companies like Airbnb or Uber simply connect the two with a service available to them through the phone in their pocket.

The Kalispell City Council last month passed an ordinance permitting short-term vacation rentals to operate within the city. Short-term vacation rentals, like those found on Airbnb or VRBO, are the real-estate branch of the sharing economy. The council worked and reworked its ordinance over most of 2016, holding more than a dozen meetings and work sessions on the matter.

Although Kalispell was among the first half-dozen cities to attempt an ordinance to corral vacation rentals, Airbnb has been running worldwide since it launched in San Francisco in 2008. Uber launched in the same city the same year and it was first permitted to operate in Montana about 12 months ago.

Talia Heck opened her guest room to travelers on Airbnb in July, nearing the height of the tourist season. Technically, operating short-term rentals in Kalispell was illegal at the time, but the city was in the process of determining ordinances and travelers were coming in.

“There were tons of inquiries as soon as I put it on the market,” she said. “Summer was big. There were days I was getting (inquiries) every hour.”

Heck lives in a brand new subdivision in north Kalispell and was one of the first residents to move in on the block. Her new home was a big hit with travelers who came into the Flathead for business, fishing, hiking and craft fairs. This was a financial anchor for Heck, a 23-year-old working part-time at Sportsman & Ski Haus while taking online classes to obtain a business degree from Montana State University. Airbnb takes a cut from each rental, so Heck never has to pay Airbnb directly for the service.

“Renting out five nights a month is like having a third roommate without having to live with a third person,” she said.

WHEN THE Kalispell City Council worked to complete its policy puzzle in framing its short-term rental regulations, the local governing body wasn’t looking to restrict small business in the city. Planning department staffers found while researching how rentals had affected other cities that while short-term rentals did bring new vacationers and spenders into the area, it had also reworked much of the community fabric.

City planner P.J. Sorensen said the effect had a range of situations and responses in different locations. New York City outlawed short-term rentals in the city, while the state of Arizona prohibited cities from prohibiting them. Some places look to keep rental owners from taking affordable homes off the market, while others won’t deny travelers en route to their local economy.

“There’s a real variety in how they wind up dealing with it in the end, but the issues are the same,” Sorensen said. “They’re looking at density, traffic issues and maintaining the character of the neighborhood.”

Kalispell’s main issue was keeping the residential areas from becoming over-saturated with rentals, to a point where neighbors would be switched out for weekly travelers.

“The reason that was in the forefront is because of areas like Durango and Breckenridge, where the majority of the city is VRBOs and Airbnbs,” Sorensen said. He said in those Colorado ski resort towns, some areas with about 6,000 homes, about 4,000 homeowners were renting their spaces online.

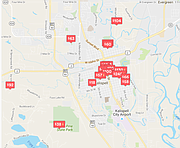

In Kalispell, searching online services like Airbnb, VRBO and Craigslist brought up about 45 short-term rentals. Compared to the near 9,000 homes within city limits, city officials know they’re not reaching the degree of Durango, but the city ended up installing a 2-percent cap on short-term rentals within the city, along with a short list of registrations with the city and state, to keep that number low. Sorensen said many other cities around the U.S. passed a similar measure for short-term rentals, although the end results still vary. In Bozeman, the city commission put a temporary ban on vacation rental permits until the city can get a hold on the increasing number of rentals. Meanwhile, Kalispell’s ordinance is not set in stone, as council members have indicated that some density protections could be added later on.

RIDE-SHARING companies had a more tangible foe when entering the Montana market, much like the battle that’s still being waged in other markets around the U.S.

Uber launched in August, but couldn’t do so until after the Montana Public Service Commission approved the company’s license to operate in the state in December 2015.

Ray Pearson was the first to sign up to drive for Uber in the Flathead in August. He works armed security for his day job, and outside those 40 hours, his driving shifts can be as long as he wants. He said in a typical Uber shift, he drives between two and 16 people.

“I like it, I meet a lot of interesting people,” he said, when driving people around town, to Glacier National Park or Whitefish Mountain Resort.

Like the vacation rentals, most of Pearson’s customers aren’t locals, but travelers looking for a quick ride rather than renting a car.

“Sometimes I wish I could record their stories. I look at myself as a tour guide. I try to tell them about all the things to do here.”

Traditional taxi companies lobbied hard against Uber’s regulation-free entry into the market and caught the ear of at least one commissioner, Bob Lake, R-Hamilton, who was the only one to vote against approving Uber’s license.

“I don’t believe, in my mind, the taxi owners, the current people that are licensed and regulated, were listened to,” Lake told the Inter Lake.

Lake said he’s not against Uber or business, he just wanted to see a level playing field. While taxi companies have to meet state standards and regulations, Uber implements its own vehicle inspections and insurance regulations, and generally disregards state rules because it hires drivers as independent contractors. Lake said getting into the taxi business in Montana can be costly, while Uber drivers have the advantage of filling a short check-list with the company before they’re ready to go.

Randy Cowger, owner of Glacier Taxi in Columbia Falls, wrote a letter to the Inter Lake in August echoing Lake’s statements. He noted the fees his company has to pay to the local airport, city of Whitefish, Montana Public Service Commission and the state are not duplicated for Uber.

“They basically have a free ride, which makes me wonder why the people who wrote the bill to allow this out-of-state entity hate taxis so much,” he wrote.

Lake recognizes that the business world has created a new way for people to make an income, but he said if the companies go too far in undercutting other companies or begin taking advantage of customers, he will likely be the one to intervene.

“Is it convenient? Yes. Is it a new world we live in? Yes. But is it in the best interest of the people? If they don’t take care of people, they won’t be in business,” he said. But, he added that, like many places around the country, regulators are still working out the kinks of the new services in order to best serve consumers.

“You have either a regulated society or not,” he wrote. “You can’t blend the two and have successful service to the people.”