Swan River teacher uses technology to enhance students' experiences

Swan River School is making its mark in how rural schools access and use technology in the classroom.

Leading the way is fifth-grade teacher Shelley Emslie, who was recently featured on the cover of “EdTech” magazine highlighting how Swan River arrived at, and uses, G Suite for Education to meet the needs of a rural school. G Suite for Education is a collection of free cloud-based tools, apps and services created by Google. She also trains other educators through the Northwest Montana Educational Cooperative and Montana-based Beyond the Chalk.

It’s not unusual for regular classroom teachers to take on a variety of subjects, roles and initiatives in a small school, but Emslie didn’t imagine she’d become a Google for Education Certified Trainer and Swan River’s G Suite administrator until she hit a roadblock in applying for a technology grant three years ago. Up to this point, staff had been using a variety of email services for school business and there wasn’t an official school district domain name for Swan River.

“At the end of the grant I put in my Gmail account and they said you can’t have a personal email you have to have a school email to verify that I was a teacher,” Emslie said.

After talking with Bud Gaiser, who is both the school’s P.E. teacher and the Information Technology person, she reached out to the Office of Public Instruction to find out how the email issue could be remedied and was told to check out Google’s educational offerings. So she did and signed up.

Now, Emslie plans to apply to become a certified Google Innovator, which means she will have to pass another series of tests and interviews. If approved, she will attend a three-day academy at Google headquarters.

“I may be a catalyst, but everyone is taking and applying what makes sense in his or her own classroom,” Emslie said, whether it’s differentiating learning, coding, recording podcasts, writing a school newsletter, 3-D printing, creating digital portfolios, sharing or connecting with pen pals and explorers across the globe.

On Oct. 30, students in Emslie’s classroom were busy typing on Chromebooks. Seated on an exercise ball, fifth-grader Will Gross picked up a book and opened to a page that he took a picture of an uploaded. He explained that it is part of an assignment called a “Book Snap.” In addition to learning subject content such as reading and writing students are developing technology skills.

“What they learn is how to download it as a JPEG. Insert it as a Google Doc and from that Google Doc they get a shareable link and turn it into a Google Form that I’ve assigned in class for them,” she said.

In turn, the students also serve as digital leaders, helping younger students begin to learn.

Writing by hand is not yet obsolete. When the Internet goes down the pencils and paper come out to pick up where students leave off, according to fifth-grader Sophie Elhajj. Emslie said that students still practice writing by hand.

“We still do written paragraphs and rough drafts and we go through and do some editing,” Emslie said.

DESPITE TECHNOLOGY being an integral tool in the classroom, dedicated state funding is virtually nonexistent. Rather, funding technology has become more reliant using general funds, passing levies, or securing grants.

While at least eight school districts have technology levies on the books, according to the Flathead County Superintendent of Schools, Swan River is not one of them, yet it continues to make strides.

The school district budgeted $1,000 from the general fund for technology this school year, according to district clerk Dee Johnson. The school’s 74 Chromebooks, which are shared among the school’s 169 students, were purchased through grants and donations.

“All these Chromebooks are not out of general budget,” Emslie said, noting that the first several Chromebooks were donated by her mother and her mother’s quilting friends. Emslie also pays for all travel expenses related to Google training out-of-pocket.

The school’s first 3-D printer was donated by the founder of Robo 3-D. Another was purchased by money raised on www.DonorsChoose.org — a site that raises funds for classrooms. Even parents like Brandy Opfar, having seen the possibilities technology offers when her child was in Emslie’s class, donated two 3-D printer to the school.

Eric Thorsen, a local artist and a parent of a fifth-grader in Emslie’s class, is volunteering to help teach staff and students how to create the 3-D model files for the printers.

“My past has been sculpting in clay and carving in wood and about 10 years ago I made the transition into working with this digital technology,” Thorsen said.

Of course, it’s a learning process of trial and error Emslie said picking up a basket of botched attempts and held up a tangle of what scribbles look like in 3-D.

“This was supposed to be a beetle,” Emslie said with a smile.

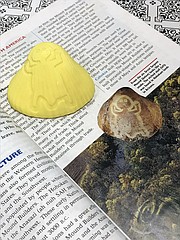

Thorsen then showed a successfully printed replica of an ancient artifact using a photo from a student textbook that can now be passed around and handled.

“You’re bringing it to life for the students,” Thorsen said, setting it next to the textbook photo.

SOMETIMES WHEN teachers get new devices, they find out the infrastructure isn’t quite there to support it, such as connectivity, which is an issue in rural schools where even cellphone service can be spotty.

“I definitely put the cart before the horse in getting infrastructure figured out,” Emslie said, but with limited resources and teachers taking the lead, she asked, “how do you know if you don’t try?”

Recently the school qualified for the E-Rate program implemented through the Federal Communications Commission. E-Rate offers discounts for telecommunications, internet access and connectivity to eligible schools and libraries.

A recent walk through of the building allowed staff to pinpoint where upgrades in cabling and wireless access points will be made, according to Emslie.

This may help out the “Wi-Fi vortex” in middle school teacher Shanna Burchwell’s classroom, where students have trouble getting onto wireless networks.

What will the upgrades do for Swan River?

“Connectivity — like that,” Emslie said, snapping her fingers. “Kids will be able to walk from one room to the other and not have to switch networks.”

Burchwell, who teaches English, French and social studies, used to teach in Alaska and knows how access to technology can level the playing field among rural and urban schools.

“It allows them to have a leg up and an equal opportunity for learning,” Burchwell said.

In addition to improving work flow, teachers can also follow individual student progress and thinking process with the ability to view revision history, or when a paper is peer-edited to see how much work students contribute to a group project.

While there is a lot of good technology, schools still have to pay attention to student privacy laws at the federal and state level and be mindful of how providers collect, store and potentially use data.

Keeping up with new tech can also be overwhelming.

“It may be time-consuming in the beginning but your work flow and your student engagement will be so drastically different that you’ll be bouncing around the classroom just awe-inspired by what we’re doing — that inspires the passion,” Emslie said.

Whether it’s the equipment or the teacher — failures become teaching moments in troubleshooting, improvisation, patience and planning.

“You have to be able to be OK with failure in front of students,” she said.

And Oct. 30 was no different.

After finishing the Book Snaps, the students, joined by a sixth-grade class, started a Google Hangout with explorer Jamie Buchanan-Dunlop who is stationed at the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences in Bermuda. Buchanan-Dunlop is the founder of Digital Explorer, a program that connects students with explorers, scientists and teachers around the world.

On a TV in front of the classroom, Buchanan-Dunlop appeared on screen to teach about coral reefs.

“So fantastic. I can see you perfectly, but there’s no audio coming from your side,” Buchanan-Dunlop said.

After trying to re-connect without success, the group decided to move on because the class can still hear him talk.

“We’ll crack on. I’m going to show you one of these to start off with,” he said holding up brain coral to student replies of “whoa.”

“I can imagine all of you in the class can reckon what this looks like,” Buchanan-Dunlop said.

Sidestepping the absent audio feed on Buchanan-Dunlop’s end, students communicated by raising their hands to answer questions. After talking about the composition of coral reefs he showed the class videos of coral polyps in action under a microscope — much to their delight. While he attempted to go outside show video of live coral, the video and audio feed cut out.

“How many of you get dropped calls,” Emslie asked the class. “If we have to reconnect we’ll reconnect — not a big deal.”

After a moment, the audio returned on both on both ends, but the video did not. The class had already planned to ask a series of “Un-Googleable” questions, such as where his passion for the ocean came from, which they were able to do before signing off.

Emslie then showed students just how far Bermuda was from Bigfork using Google Earth. Starting from a perspective of Earth from outer space, the program zoomed in on Bigfork then whizzed over the ocean stopping at the island.

“It helps people understand,” fifth-grader Kennady Garvin said, summing up what technology does.

Reporter Hilary Matheson may be reached at 758-4431 or hmatheson@dailyinterlake.com.