KMS history lesson includes grinding wheat, churning butter

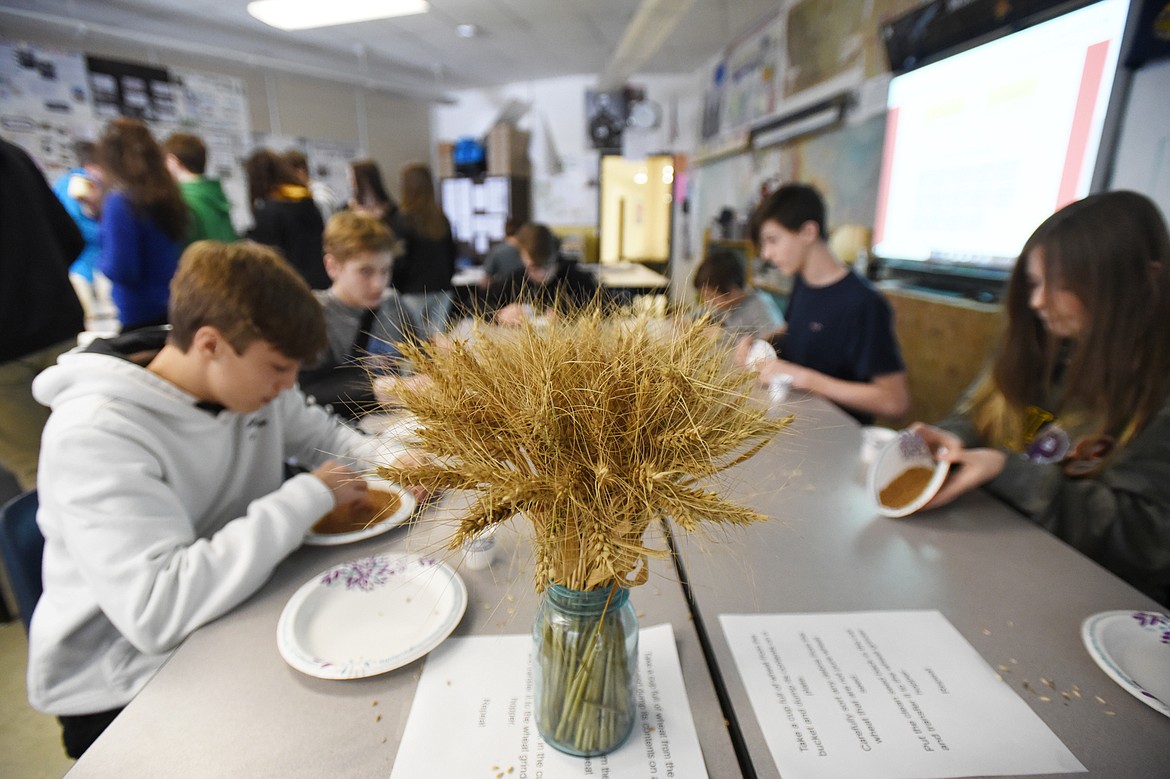

In Montana History teacher Kris Schreiner’s classroom at Kalispell Middle School there was an uncustomary setup on Tuesday — a pail of winter wheat, grain mill, strainer, half-gallons of heavy whipping cream, jars and heart-rate monitors.

Eighth-graders filed into the room to face the morning’s activities: making flour and butter by hand. The heart-rate monitors were used to monitor beats per minute. Schreiner said students would use the information to chart the calories burned by making the food products. Then, they calculated the potential calorie intake of the final products.

The activities cap a farming and ranching history unit with a mix of math, cardio and culinary arts.

Eighth-grader Aidan McShane said students learned about the hardships of farming and ranching through Montana’s history.

“And how much it’s changed to now,” eighth-grader Trey Roo said.

“We’re a huge wheat producer,” Schreiner said about Montana agriculture. “We also produce a lot of sugar on the east side of state with sugar beets. In our area here, we have a lot of wheat. We also have a lot of canola. We are a big malt barley state also.”

Eight-grader Ava Chorn said students also did a simulation where they bought farmland and grew crops, figured out equipment costs, production rates and created trend lines.

“All of those operating costs, in a lot of cases, come close to outweighing the actual value of the product,” Schreiner later noted as a big challenge of modern farming, in addition to land value.

“In the end we are still left with the pressing question — what is to become of our family farms and ranches as land prices and operating costs spike and product prices fail to follow suit?” he asked.

The class of 28 was paired off, but it took the effort of the entire classes to make enough flour to bake bread at the end of the week.

“Much like our farm communities of old would have done to help support one another, students will find that doing this kind of work alone was not sustainable; they needed each other in order to make it,” Schreiner said.

Schreiner explained how to operate the grain mill.

“... If you get a little over center on the top of it, it’s a little easier,” he said cranking the handle. “If you’re further back you gotta use more, kind of like a shoulder and elbow motion. It might wear you out quicker.”

The most important takeaway — “even if you’re not collecting data we need this wheel turning,” he said. “We need to produce flour because if we don’t get enough flour we’re going to have a whole lot of butter for not a whole lot of bread.”

Eighth-grader Trey Roo was the first to take the helm. With the heart-rate monitor on one hand, he placed it on the table. The other hand he placed on the grain mill handle. Eighth-grader Aidan McShane turned on a stopwatch. Each group had a two-minute turn.

The wheel of the grain mill squeaked into motion. Roo began to lose his breath after 20 seconds. McShane rallied him on the grain flowed into a small container and looked like piles of sand.

At about 90 seconds Roo paused to rest, then continued.

“Thirty seconds left,” McShane said. “Fifteen. Two, one, zero!”

McShane decided to use both arms and turned the wheel as fast and he could, but soon, ground to a halt.

“I’m dead,” he said.

“Thirty seconds in,” Roo said.

“Thirty seconds in?” McShane said.

Both said grinding the grain was tougher than it looked.

“Thirty seconds in felt like two minutes,” they agreed.

Students at an adjacent table refilled the mill with “clean” grain that came from Schreiner’s family’s farm in Eastern Montana.

“We’re taking all this crud out, trying to get it down to the grain,” said eighth-grader Rylan Pevey, noting “crud” such as husks, rocks, other seeds, insects, for example.

Harvesting wheat in the past would be part of the task of a threshing machine, and today, a combine.

Over at the butter-churning station students vigorously shook the small glass jars filled with heavy whipping cream donated by Kalispell Kreamery. Within minutes, some are surprised to see it begin to solidify.

Earlier, Schreiner described the butter-making process.

“Your heavy whipping cream is going to turn into whip cream first. The liquid is going to disappear and you’re going to go, ‘what happened?’ Keep shaking. The more you shake the more it will start to recollect and you will get a lump of butter and buttermilk on the outside of it.”

Students then brought their jars to a strainer perched on a mason jar. Turning the jars upside down, blobs of butter fell out, while the buttermilk collected in the jar underneath. Some students didn’t like the lumpiness of the raw butter, but eventually it was smoothed together by eighth-grader Ava Chorn, who patted together each batch into a log.

At the end of the class period Schreiner held up the container of wheat the class had worked hard to grind.

“It’s about three cups,” he said.

Over the next two days, the students used the flour to bake bread, topping it off with the butter they churned and washing it down with buttermilk.

Reporter Hilary Matheson may be reached at 758-4431 or hmatheson@dailyinterlake.com.