Families recount loved ones’ declines at Whitefish facility

In a recorded video chat dated Aug. 18, Deb Johnson can be heard coaching her 92-year-old father, Alton “Ott” Johnson, through a breathing exercise.

“Smell the roses, blow out the candles,” she instructs.

Although he is responsive to his daughter’s words, Ott appears uncomfortable. He is leaning into the left side of his wheelchair, as if to alleviate pain on the right side of his body. The hair on his head and face is uncharacteristically long and unkempt. His breathing is heavy.

“Smell the roses, blow out the candles...”

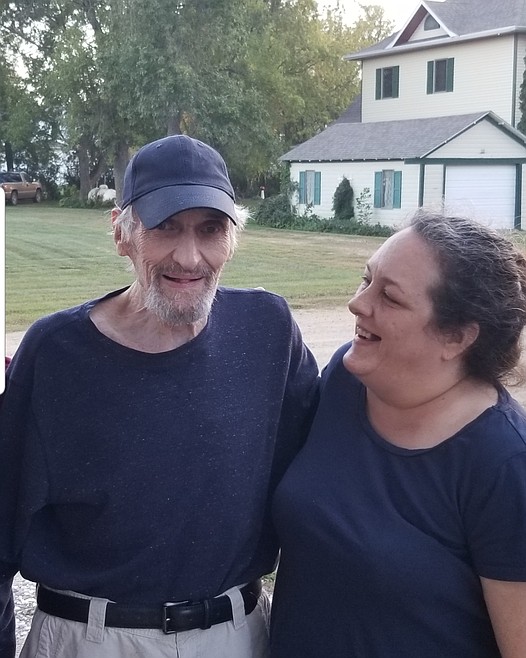

At the time of the call, Ott was about 60 days into his three-month stay at the Whitefish Care and Rehabilitation Center. From the time he was placed in the facility in early June, Johnson said she watched her father grow thin, pale and cognitively unresponsive, though his decline came in waves.

“He had gone from being able to stand up with barely any assistance to not being able to stand unless two people were holding him. His good leg had completely atrophied at a rehab center where his health was supposed to improve,” Johnson said of her father, who was placed in the facility to undergo rehabilitation post-surgery. “It killed me to watch him go downhill in there.”

Three days after that Aug. 18 video call, facility officials reported 14 residents and staff had tested positive for COVID-19. Within one week 41 individuals — Ott included — had tested positive and four residents had died. That death tally would soon grow to 13 residents as the facility struggled to control an outbreak some allege they were not equipped to handle.

And on Labor Day, one day before Johnson and her family were scheduled to remove Ott from the facility’s care, his name was added to the center’s list of COVID-19 fatalities.

In a separate recorded video chat from the morning before he passed, the screen displays a version of Ott that is completely foreign to his daughter. He doesn’t react when Johnson speaks, his eyes are sunken, he is struggling to stay awake during the call and his breath is raspy. He can be seen looking around his room at one point asking, “How do you catch an eye?”

That video call was placed at 10:06 a.m. At 3:45 p.m., a staff member called Johnson to inform her that her father had passed.

“He was lying there, just completely out of it,” Johnson said. “Why didn’t they do anything?”

In other video chats leading up to that day, nurses can be viewed entering his room without personal protective equipment amid the center’s outbreak and at one point Ott told his daughter he had been given a roommate — two violations that align with findings in a state investigation report that found Whitefish Care failed to protect its residents from COVID-19.

Reid Crickmore, executive director of Whitefish Care and Rehab, said the facility is working toward rectifying issues discovered during the COVID-19 survey and said other deficiencies cited in the spring at the start of the pandemic have been addressed.

“We unfortunately lost 13 residents to COVID-19 and our deepest condolences go out to those families. As a facility we take the deaths of our residents like they are our own family,” Crickmore said via email.

The most recent survey conducted at Whitefish Care took place on Sept. 22. According to Crickmore, no deficiencies were found.

JOHNSON FIRMLY believes her father’s death was accelerated by neglect and a failure to ensure staff could safeguard residents from a virus widely known to adversely impact older adults. She is not alone in her beliefs.

Several individuals who have had a family member or friend in the facility in recent months contacted the Daily Inter Lake to discuss their experiences with Whitefish Care’s management and staff.

Their stories have similar themes, many of which are familiar to deficiencies detailed in past reports on the facility. Among other allegations, all of those interviewed said staff and management rarely made contact with the families, even as COVID-19 ravaged the center, their loved ones went extensive periods of time without being washed, detailed assessments and rehab plans were not provided and personal items went missing, among other issues.

Johnson said it wasn’t unusual for her to go more than a week without hearing from staff, and when she finally got a hold of someone to ask basic questions about her father’s care, she said they would always reply “we’ll look into it and get back to you.”

JULIE BISHOP, whose father first entered the facility in July, said she and her mother were told at the beginning of his stay they should “expect weekly emails on his progress,” which rarely occurred, and they didn’t receive an initial assessment for weeks. And when Bishop and others called, the majority of their calls were met with a voicemail instead of a human.

Bishop’s dad died from COVID-19-related problems less than two weeks after they pulled him from Whitefish Care in early September. She said failed communication was only the start of their issues with the center.

On multiple occasions, Bishop and others would show up to the facility to speak with her father through a window. During a July 7 visit, her dad was in “very soiled sweatpants” and “his glasses were broken,” which staff eventually explained was a result of her dad, who was practically wheelchair-bound at the time, “falling through a glass door.” There were multiple times Bishop’s father would be in completely soiled outfits that weren’t his own.

“He was a Marine. He wore the same standard clothes, but from head-to-toe he was always wearing an outfit that he would never wear. They never knew where his clothes were even,” Bishop said. “He kept on saying to us ‘I want out of here.’”

On the topic of missing items, Serenity Frantzen said her 88-year-old father Robert Marr departed a veterans home and entered the facility for rehab in July with his wallet, among other items. Frantzen said staff claimed he came with nothing, but then one night “the wallet magically turned up.” Frantzen alleged the facility falsified her father’s intake papers, saying he was possibly COVID-19-positive and homeless as well — two descriptors she said did not match up with the veteran home’s discharge paperwork.

ALL INDIVIDUALS interviewed said generally, the health and hygiene of their loved ones plummeted under the watch of Whitefish Care.

Upon entering the facility, Johnson said her dad could “fill out” his shirts, but in a Sept. 3 video, his sweater is visibly drooping off his shoulders and his fingernails, which he held up to the screen, were black.

Bishop, who said her dad’s meals sometimes resembled “prison food,” said her father could barely roll his wheelchair to the window, despite the family being told he was receiving occupational therapy on a daily basis.

And when Frantzen pulled her dad out of Whitefish Care more than one week ago now, she estimated he had lost 30 to 40 pounds.

“If it wasn’t for one nurse with a good conscience who came around eventually that seemed to really care, my dad would be dead,” Frantzen said. “He had completely regressed. What recourse do residents have when they have nowhere to go? COVID has created blanket opportunities for senior citizens to be treated poorly behind closed doors.”

Frantzen's father was one of the lucky ones.

And accounts from those with familial connections to the facility, combined with myriad past deficiencies, beg the question, when might a facility be forced to shut down?

JON EBELT, spokesperson for the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, said oversight of these facilities “ensures identified deficiencies are corrected.” Once an initial survey is conducted, follow-up surveys take place to see if management and staff corrected the problems.

“It’s our goal to work with facilities to make sure they are in compliance with changing federal rules and requirements to ensure those living in these facilities are safe,” Ebelt said.

Montana is home to 70 CMS-certified long-term care facilities, about a dozen of which have reported COVID-19 cases. In recent years, 14 of those have experienced serious deficiencies and 56 homes have been cited for infection-related deficiencies.

Those that have been cited for fine-worthy issues have collectively paid nearly $2.9 million in penalties, according to the CMS Nursing Home Inspect website.

Reporter Kianna Gardner can be reached at 758-4407 or kgardner@dailyinterlake.com