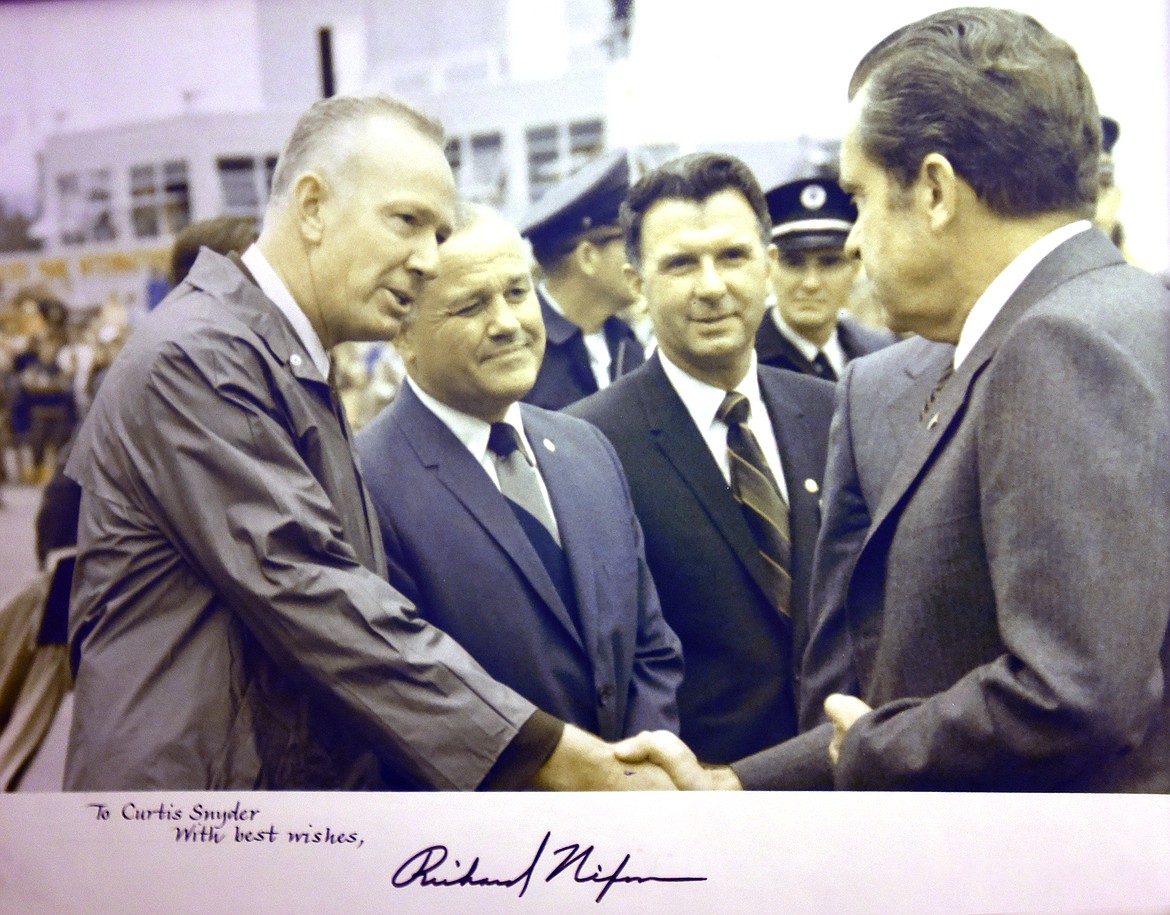

Kalispell's oldest living ex-cop recounts storied career

Curtis J. Snyder, 93, saw a little bit of everything during his 41 years in law enforcement....

Support Local News

You have read all of your free articles this month. Select a plan below to start your subscription today.

Already a subscriber? Login

Daily Inter Lake - everything

Print delivery, e-edition and unlimited website access

- $26.24 per month

Daily Inter Lake - unlimited website access

- $9.95 per month