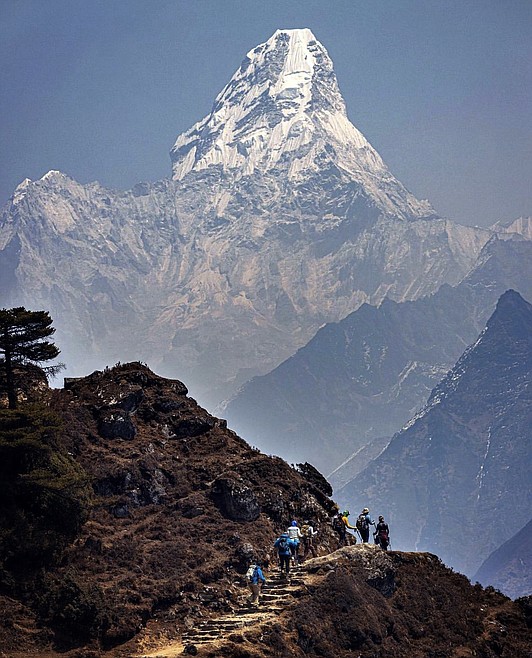

Flathead man achieves dream of summiting Mount Everest

Forty-nine year old Steve Stevens has hit the wall. Sweating profusely and not feeling his best, he finds a large rock on which to take a break from his long climb....

Support Local News

You have read all of your free articles this month. Select a plan below to start your subscription today.

Already a subscriber? Login

Daily Inter Lake - everything

Print delivery, e-edition and unlimited website access

- $26.24 per month

Daily Inter Lake - unlimited website access

- $9.95 per month