Lawsuit against Libby clinic centers on lung scans

Patricia Denny and her husband, Jeff, had hoped to one day get an RV and travel the country. Instead, Jeff has been forced into retirement at age 54 by a lung disease caused by the asbestos that’s polluted the small town of Libby, Montana, for decades.

Jeff Denny’s lungs are damaged from the asbestos he breathed while participating in an Environmental Protection Agency-run cleanup of the asbestos contamination caused by the vermiculite mine that closed 30 years ago in this community in the Cabinet Mountains. Patricia Denny is afraid she will get asbestos-related disease as well, given how many residents of the town have become sick. Barbed fibers, a byproduct of vermiculite, attach to the lungs when breathed in.

At least 400 people exposed to Libby asbestos have died of asbestosis, mesothelioma or other lung diseases, and thousands more have been diagnosed with lung damage and diseases caused by asbestos, according to the Center for Asbestos Related Disease, the Libby clinic that diagnosed Jeff Denny.

“It is not the matter of if, it is when,” Patricia Denny said in an online message. “Once this barbed killer gets in ya it stays … and kills the area it penetrates.”

The company that operated the mine, W.R. Grace, filed for bankruptcy in 2001, as thousands of lawsuits poured in after the extent of the contamination became known. Since then, the Montana Supreme Court has held several other companies responsible as well, including the BNSF Railway, one of the nation’s largest rail companies. BNSF, owned by billionaire Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, is liable for spreading asbestos amid the dust that blew off its cars while transporting vermiculite across the nation for use in insulation and other purposes, according to court rulings.

Now, the railroad is going after the local health clinic that opened to deal with the health crisis in 2000 and still screens dozens of people each month as new cases emerge. BNSF is suing the Center for Asbestos Related Disease in federal court.

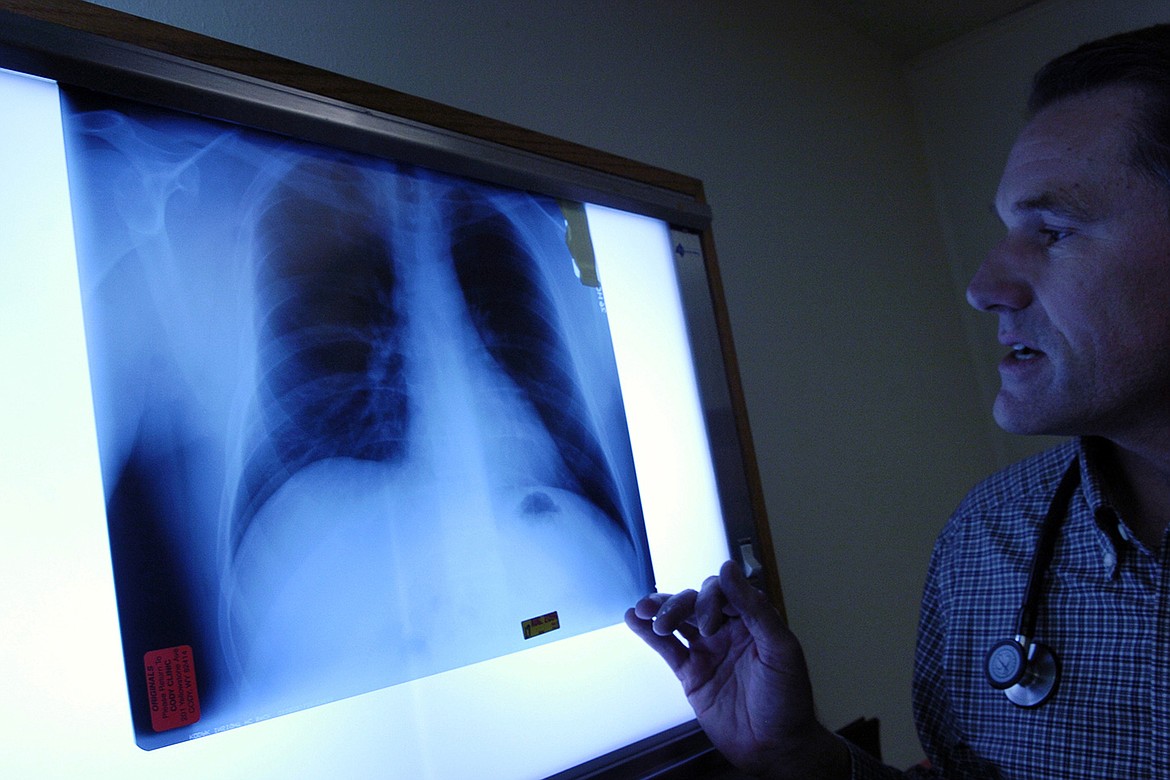

The rail company alleges that the clinic is defrauding Medicare and grant agencies by overdiagnosing asbestos-related diseases and running unnecessary tests. BNSF also takes issue with CARD’s reliance on X-rays or CT scans to make its diagnoses, even if independent experts disagree with the clinic’s interpretations of the scans.

“CARD knowingly billed the federal government millions of taxpayer dollars for medically unnecessary radiographic studies and interpretations that they routinely disregarded,” BNSF spokesperson Lena Kent said in a statement.

In the suit, which was filed in 2019 but not made public until Feb. 18, BNSF asked the U.S. government to prosecute CARD for fraud. The government declined, leaving BNSF to sue the clinic itself under a federal whistleblower statute.

Kent said that the decision “was not taken lightly” and that BNSF “recognizes the extraordinary impact that Asbestos-Related Disease has had on the [Libby] community.”

CARD’s team is one of the few who study the health effects of Libby amphibole asbestos — the name of the needle-like mineral found only in Libby and a few other mines around the world. The clinic is also the leading provider of asbestos diagnostics and care in the 2,700-person town, where mesothelioma and asbestosis are rampant.

CARD and its lawyers see the lawsuit as a ploy to damage the clinic’s credibility and limit the railroad’s financial liability by casting doubt on the legitimacy of the clinic’s diagnoses. The attorney representing CARD, Tim Bechtold, said the lawsuit is taking the clinic’s time and resources away from patients. “All they want to do is hassle CARD,” he said. “It’s completely cynical.”

The EPA declared Libby a Superfund site in 2002 and spent more than $600 million on the cleanup, according to the agency. W.R. Grace agreed to pay current and future asbestos victims’ medical costs and $250 million for the cleanup, and the company emerged from bankruptcy in 2014.

People in Libby are still being diagnosed with asbestos-related diseases today. Decades can pass between exposure and the development of symptoms, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Anyone in Libby can qualify for Medicare if they develop lung disease, under a special part of the Affordable Care Act.

The crux of BNSF’s accusations is that many of CARD’s diagnoses of distinct lung diseases in Libby residents are fraudulent, largely due to their rarity and the difficulty that others have diagnosing them.

Researchers from CARD and Mount Sinai hospital in New York City have found that CT scans from the lungs of people exposed to amphibole showed a distinct type of scar tissue called lamellar pleural thickening (LPT). CARD’s research suggests that this scar tissue thickens over time and makes it increasingly difficult for the patient to breathe.

But few, if any, cases of asbestos-associated LPT have been diagnosed outside of CARD. The clinic said that is because no one else knows to look for it. “The disease is different than typical [asbestos-related] disease so it does in fact take a trained eye to identify it,” CARD said in a statement. “If the [CT] reader did not know what he/she was looking for, then it would not be identified.”

Others see this as evidence that CARD is overdiagnosing patients with a condition that may not exist. “I was appalled by what goes on in Libby,” said Dr. Anthony Dal Nogare, a pulmonologist at Kalispell Regional Healthcare who has testified for BNSF in prior lawsuits. “It’s like the emperor’s new clothes if it’s something only they can see and no one else can.”

Dal Nogare, who visits Libby frequently to see patients, said he never sees LPT on CT scans and rarely sees asbestos-related lung diseases in people who did not work in the mine. He pointed out that the smoking rates in Libby are high, which could account for the shortness of breath and other symptoms CARD’s patients experience.

CARD said it sends each of its CT scans to independent radiologists who can confirm the diagnosis of LPT. The clinic’s records indicate it finds abnormalities in 60% of scans, while the outside radiologists find them in only 35%. CARD’s administrative director, Tracy McNew, said the discrepancy occurs because the independent radiologists don’t receive any clinical information about patients or their symptoms, meaning they can’t learn how to see LPT and associate it with the disease.

“It’s just not an exact science,” said Bruce Alexander, an environmental epidemiologist at Colorado State University. Although something serious like mesothelioma would be obvious in a CT scan or X-ray, he said, trained radiologists can differ on how to interpret subtle signs like pleural thickening, which may be confused with fat on the lungs.

Dr. Paul Scanlon, a pulmonologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, said most radiologists would read what CARD calls LPT as pleural plaques, which are difficult to mistake on a CT scan. Pleural plaques are an indication that someone has been exposed to asbestos but are not very harmful by themselves.

CARD declined to make its medical experts available to respond, citing the pending case.

“There’s legitimate scientific debate about what the implications of these exposures are, but it’s pretty clear people in these communities were adversely affected,” Alexander said. In 2012, he studied the lungs of Minneapolis residents who lived near a plant that processed Libby vermiculite. He found about 11% of the residents there had a type of pleural thickening or plaques but said the long-term health implications are unclear.

Other evidence suggests that the lungs of Libby’s residents are especially damaged, both those of people who worked in the mine and those who did not. In 2017, the CDC published a study showing that residents were more than 100 times as likely to die of the lung disease asbestosis than the general population.

“Simply by living in Libby, they were exposed to asbestos at a high-enough concentration,” said paper author Samantha Naik, a former CDC epidemiologist who is now a private consultant. She said Libby represents a rare case in which an environmental chemical can be scientifically proven to cause a disease.

For her part, Patricia Denny is frustrated that BNSF and other companies have yet to be held fully accountable.

“They all made a huge profit, still are, while the people are dying,” she said.

Sara Reardon is a reporter for Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit news organization providing information on health issues in the U.S.