Timber management project aims to mimic natural process

Hundreds of harvested lodgepole pine released a clean, sweet smell with a touch of mint, into the air as they lay in piles on the landing floor.

Just outside of Coram on the Flathead National Forest independent contractors have gathered for a logging operation under a contract with Weyerhaeuser.

Forests have a life cycle, according to Paul Donnellon, a supervisory forester with the Flathead Forest who is visiting the site on this day. Trees grow, and they compete with each other — some die, some live, some fall, some burn.

The Lake Five area, where the operation is located, is a prime example of the cycle of forestland life.

Forests regenerate on their own naturally, sometimes through wildfire. In 1929, the Half Moon fire burned more than 100,000 acres in the Flathead Valley and Glacier National Park, leaving the woods around Coram and Lake Five scorched black.

The trees that loggers are currently harvesting are the trees that grew from those ashes. The life cycle of a lodgepole is around 100 years. After that point, the wood becomes lower quality with higher mortality rates and creates more fuel for potential wildfires.

Adding structures, communities, businesses and people themselves to live alongside heavily forested areas, makes human management needed, Donnellon said.

“If we didn’t live here the forest would be just fine,” he said. “But we are a part of the environment here and part of that is managing it to meet the needs and interests of the people living here.”

According to Donnellon, timber harvesting is a tool that physically and ecologically does good work and also is economically efficient.

The land itself near Lake Five is a part of the wildland urban interface, which means it is a mix of private land, houses, businesses and national forest land. The Forest Service, while looking at long-term management goals for the forest, assessed that a logging operation would be beneficial in the area, Donnellon said.

Such projects, along with timber harvest, also include thinning and seed tree treatment, as well as vegetation treatments.

The goal via logging, Donnellon said, is to replicate that natural pattern and mimic the natural aspect of a tree’s life cycle — while managing an economic benefit.

FOREST MANAGEMENT is not new. According to Zachary Miller, a forester with Weyerhaeuser, it is a natural part of existing with the land, even dating back to before European colonization in America alone.

“We’re resetting the clock and we’re reinitiating another stand of trees,” said Miller. “[The changes are] very abrupt at specific points in time, but [the forest is] always changing. If we don’t manage the forest, it will manage us.”

According to the nonprofit Forest History Society, Native Americans have managed the land — specifically forestlands — as early as 1,000 B.C. as they cleared forestland to make room for planted crops. They set fires to improve visibility, facilitate travel, and control the habitat of the forest by getting rid of unwanted plants and encouraging the growth of more desirable ones.

The process itself to secure and begin a logging operation in the current day — like the one in Coram — is lengthy.

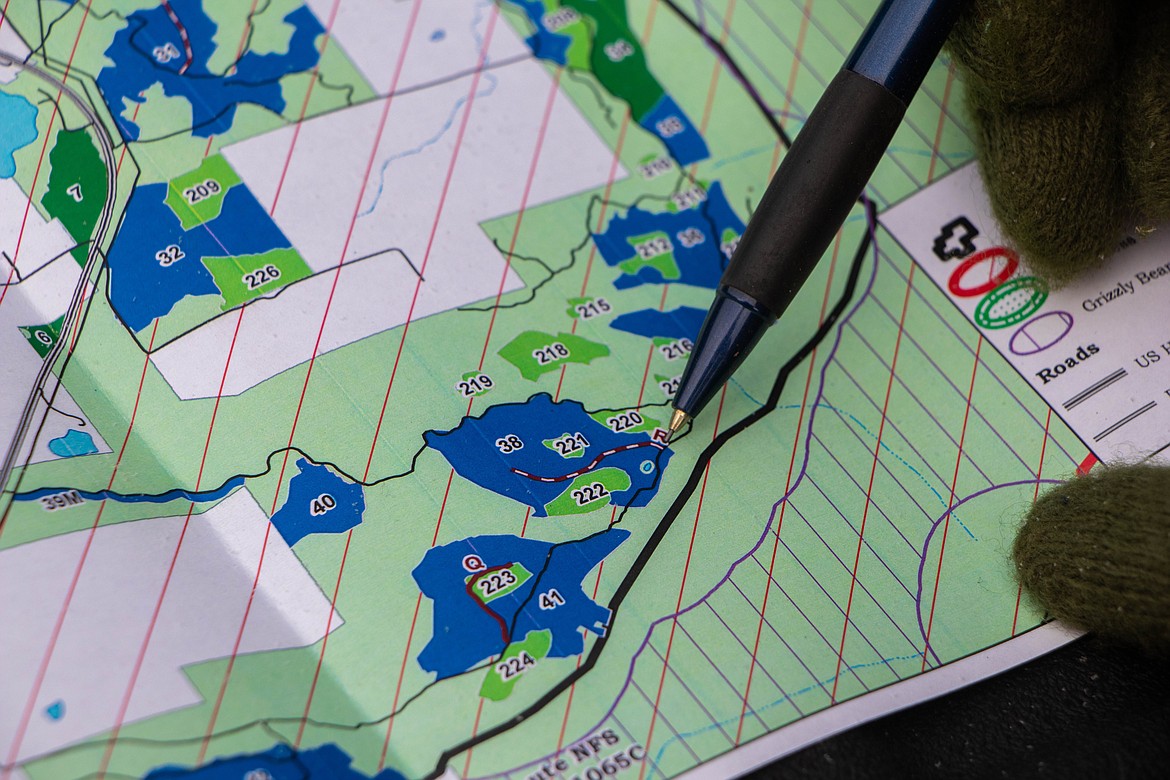

According to Donnellon, the first step is to reconnaissance the area, attribute characteristics and identify biological and water concerns, past management efforts and geography.

Once that is all done, the Forest Service creates a proposed action which gets drafted into a scoping letter, which then goes out for public review and comment. This focuses mainly on what project is proposed, not the land itself.

Once comments are received, the agency can create alternatives to the plan if necessary and establish the scale of what National Environmental Policy Act analysis needs to occur which creates the environmental assessment: identifying impacts of the operation rather than the plans of the operation itself. After public comment, a decision notice is created, a contract is written up, and units are beginning to be laid out.

The contract is publicly advertised and the higher bidder gets it. In this case, Weyerhaeuser was the higher bidder. The company pays based on stumpage, or the price on standing timber to harvest it.

The minimum bid was around $12 a ton, but the winning bid was set around $16 per ton of wood for the Lake Five project. Weyerhaeuser, as they remove the wood from the forest, owes the Forest Service that amount per ton.

Weyerhaeuser was required to hire logging contractors and companies to complete the tasks surrounding the project — creating roads to access the desired unit, operating the machinery that removes and organizes the trees and transporting trees to the mills.

The wood is then transported to mills to process and create studs, plywood, and medium density fiber. Logs that are not as large are sent to other mills to create rails, whips, pulp and wood chips.

WHILE REMOVING a stand of trees seems like a drastic change, it is just a step in their lifecycle, Donnellon contends. To an average person visiting the forest, they will never see those small nuances in a tree’s life. However, foresters do, because they are all costs in the long run.

His colleagues agree.

“You always need that continual succession on the landscape,” Miller said.

There are a lot of trees in Montana, specifically ones of high value, Donnellon said. Montana trees grow slower than trees in the South, meaning that they produce solid, strong boards.

“Montana has things to offer in terms of uniqueness in our product that we shouldn’t forgo just because we can grow trees well in the South, for example,” Donnellon said.

Using best management practices, which are used to protect water quality during timber harvests, forestland agencies view their work as a sort of “farm to table” notion. Wood is needed by Montanans for use and livelihood.

“We’re trying to create healthy, resilient, forest ecosystems,” said Tye Sundt, a forester with Weyerhasuer.

“Ones we can live in,” Miller added.

Reporter Kate Heston can be reached at kheston@dailyinterlake.com or 758-4459.