Creston research station designed to meet needs of Flathead Valley producers

Returning from a meeting, then superintendent of the Northwestern Agricultural Research Center Bob Stougaard found his desk covered in sticky notes. The messages, from farmers throughout the Flathead Valley, pleaded for information about an unfamiliar insect appearing in their fields.

Stougaard lept into action, surveying numerous fields in Flathead County in an attempt to assess the damage. What he found then in 2006 was a significant infestation of the orange wheat blossom midge, an orange bug half the size of a mosquito that wreaks havoc on spring wheat, a staple crop for local producers.

The midge lays its eggs on the wheat head, and when the larvae hatch they feed on the kernels. Unfortunately for producers, it’s impossible to determine the extent of the damage until the wheat is harvested and the kernels are inspected.

Western Canada and the Dakotas had been wrestling with the midge since the late 1980s, and it was estimated that Canada lost over $100 million in economic output each year as a result of the insect.

The aftermath of the midge’s arrival to the valley was devastating, according to Stougaard. A conservative estimate put the economic loss at more than $1.5 million in Flathead County.

“It kind of was a scary deal because we went from a situation where normally we would get 80 to 90 bushels of spring wheat per acre down to zero. Some farmers didn’t even bother to combine their wheat that first year back in 2006. It just wasn’t worth the time and effort and cost of the diesel fuel. There wasn’t anything to harvest.”

The center is celebrating its 75th anniversary this year and as those connected with the research station reflect on its decades-long history, they all agree that the orange wheat blossom midge defines one of the most consequential periods for the center.

When the Montana state Legislature voted to establish the Northwestern Montana Branch Station (now the Northwestern Agricultural Research Center), in 1947, they envisioned a research station designed specifically to meet the needs of producers in the Flathead Valley and surrounding counties.

Montana State University opened its doors in 1893, as part of the land grant university system, which provided land and funding from the federal government to the states with an intent to “benefit the agricultural and mechanical arts,” according to the Morrill Land Grant College Act of 1862.

The Hatch Act of 1887 further developed the vision for land grant universities, according to the United States Department of Agriculture, providing funding for schools to establish agricultural experiment stations that would conduct research with the aims of improving agricultural production and finding innovative solutions to the problems facing producers.

By 1947, there were already several other experiment stations operating under MSU throughout the state, but none in Northwestern Montana. Research from other stations, conducted in substantially different environments, producers realized, wasn’t applicable to their operations.

Nestled in the foothills of the Swan, Mission, and Salish mountain ranges, the Flathead Valley is a uniquely fertile environment, said Jessica Torrion, the current superintendent of the center.

“In Montana, we are one of the highest yielding environments because we have good soil, deep soil. It’s just the nature of the soil here that’s deep and fertile, and most of the time we have good rain.”

The quality soil and ample rainfall lend themselves well to crop production, in particular, hay and wheat. Yet, this environment also brings challenges. Crops thrive, but so do weeds, diseases, and insects, like the orange wheat blossom midge.

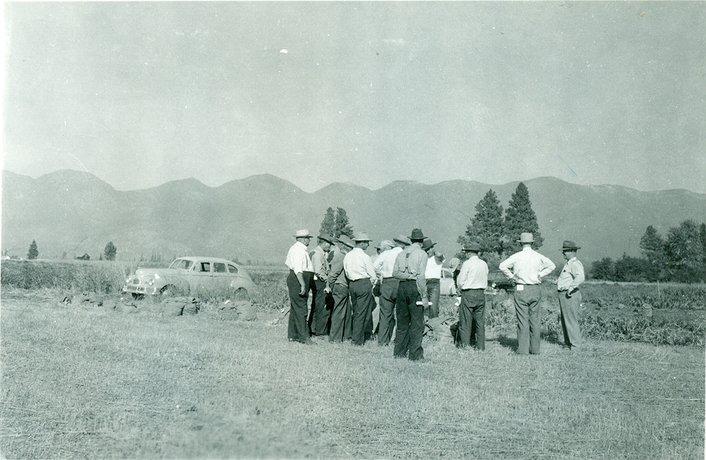

RESPONDING TO the unique challenges and blessings of the Flathead Valley would require research tailored specifically to the environment, so, in the early 1940s, members of the community from a wide variety of backgrounds came together to advocate for a research station of their own.

Flathead County submitted the first three requests to MSU in 1946, followed quickly by a total of 13 requests from Lake County between 1946 and 1947.

During the 1947 Montana state Legislature session, members introduced House Bill 271, which read “An act to establish a Branch of the Agricultural Experiment Station of the Montana State College, in Northwestern Montana, to be known as ‘Northwestern Montana Branch Station’.”

The act gave Montana State the authority to accept donations of money, implements, scientific equipment, buildings, animals, and supplies, for the purpose of establishing the Northwestern Branch Station. Montana State would implement the station, but the responsibility for providing the funds and equipment fell squarely upon the residents and producers of the Flathead Valley.

Not to be deterred by the challenge, the agricultural community lept into action. In order to coordinate the fundraising efforts, they created a central committee, with county, city, and community committees underneath to focus on more localized efforts.

Over the course of a single winter, the committee raised nearly $22,000 for the experiment station. With funding now secured, the dream of a research center was just a few steps away from reality.

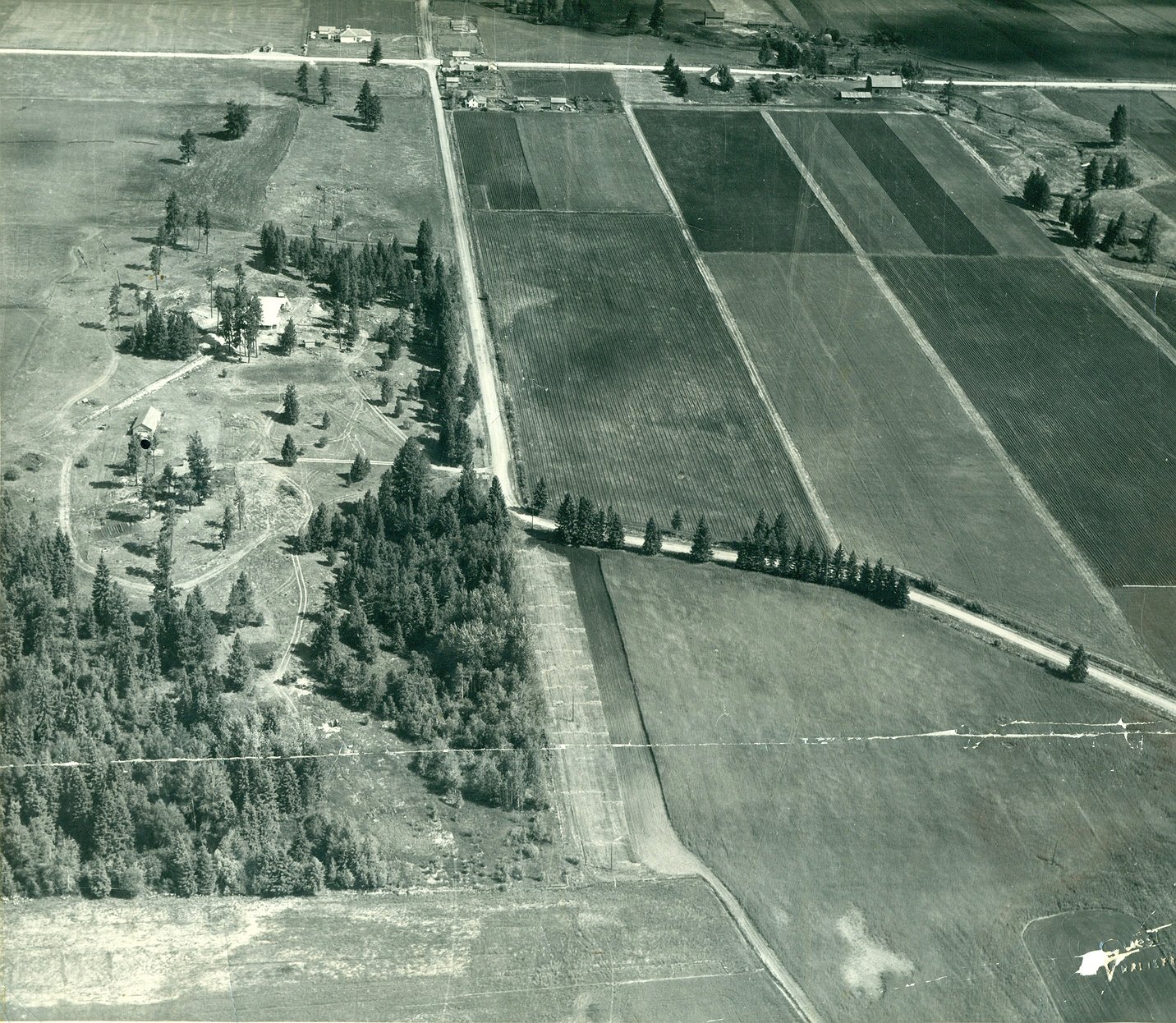

The Montana Experiment Station staff were responsible for selecting the location of the new station and ultimately settled on the present location in Creston, after considering the soil, topography, and accessibility. The initial land purchase consisted of 75 acres just off of Montana 35, 12 miles east of Kalispell.

In the spring of 1949, just three years after the community began seriously lobbying for a research station, the Northwestern Branch Station planted its first crops.

Shortly after, they held their first official Potato Day, inviting the public to join in the celebration of three years of hard work. Nearly 300 people showed up.

C.W. Roath, the former superintendent of the University of Wyoming Experiment Stations, was selected as the first superintendent of the Northwestern Montana Branch Station. He had arrived in Montana in 1946 to work with the university’s extension services, but was quickly tapped to take charge of the new center.

Roath focused on forage crops and studying the center’s flock of sheep. He traveled throughout the county, presenting the station’s research to producers.

As the decades progressed, the center continued to grow and evolve to meet the ever-changing needs of producers. An additional 150 acres were purchased in 1969, bringing the property to a total of 200 acres.

While the station initially poured significant resources into seed potato and livestock research, according to Torrion, this shifted over the years as the valley’s farmers responded to market demands and delved deeper into crops like wheat and hay.

OVER THE course of the next half-century, the station became a pillar in the farming community, building relationships that would be critical when responding to the biggest crisis in Flathead County agriculture since the establishment of the research center.

In the years following the outbreak of the orange wheat blossom midge, former superintendent Stougaard and producers devoted efforts to mitigation and learning to live with the unwelcome newcomer. The effort required tapping into the spirit of collaboration that had been a hallmark of the center from the beginning, bringing together researchers, producers, county agents, fertilizer dealers, and crop consultants.

Farming a couple thousand acres in Lake County, Ken McAlpin, who currently serves on the center’s advisory committee, vividly remembers the early efforts to combat the midge.

At the time, the only solution to the problem was spraying insecticides, which wasn’t an appealing strategy to anyone involved, McAplin explained.

“We had to spray insecticides multiple times throughout the season to knock these bugs back which obviously we don’t like to do because it costs extra money and… is not good for anybody or the environment.”

Over the next several years, Stougaard consulted with colleagues in North Dakota and Canada, researched cropping systems, and even experimented with introducing a parasitic wasp to feed on the midge.

Yet, it was clear that all of these strategies were only delaying the inevitable. In 2009, the midge began spreading to other parts of the state, increasing the urgency of the research happening at the center. If a solution wasn’t found soon, the midge could destroy Montana’s spring wheat production.

With their backs up against the wall, Stougaard and the producers turned to Luther Talbert, a spring wheat breeder working in Montana State’s wheat breeding program.

Talbert launched another collaborative effort, this time with researchers at North Dakota State University. There is only one gene in the world, called SM1, that is known to be resistant to the midge, producing a toxin that kills the insect. Through the researchers at NDSU, Talbert was able to obtain the gene, which is found in a few varieties of winter wheat in North America, and he set to work breeding this gene into spring wheat varieties suited to Northwest Montana.

The result, Stougaard said, was a new variety of wheat that saved spring wheat production in the Flathead Valley.

“The one that really performed well was a variety called Egan, after a slough in the valley where the midge was particularly prevalent. Egan not only had resistance to the midge but it also had resistance to stripe wheat rust, it had very high protein content, it had other quality attributes that made it a good wheat to plant.”

Egan became commercially available to producers in 2016, nine years after the midge first arrived in the Flathead Valley. Stougaard explained that science like this works slowly, and “it usually takes about 10 years after you make your first crosses to actually have a variety that’s ready to be released to the farming community.”

McAlpin said the Egan variety made it possible for him and other producers to grow spring wheat again, without fear of their fields getting wiped out.

“That was hugely beneficial. I still grow part of that variety even 10 years later. And the insect pressure is less than it used to be.”

Reflecting on the history of the station she now directs, Torrion thinks the orange wheat blossom midge is the preeminent example of the cooperation and innovation that the center has fostered in its 75 years since that first Potato Day in 1949.

“It’s one of the examples of an experiment station effort with the community, and it’s not just us, it’s including farmers and ideas and brainstorming what we can do together,” she said. “They allowed us to work on their farms to monitor and plant. That was just one example of where research, farmers, ideas, and hard work come together to solve a problem.”